Protecting the Right to Vote

How Foundations are Helping Ensure Americans’ Access to the Voting Booth

Democracy is precious. It means everyone’s voice being heard. Sometimes, that simple concept is lost, however.

When Marvin Brown, a 90-year-old Army Air Corps veteran, registered to vote by submitting a federal form, he discovered he needed additional proof of citizenship to cast a ballot in local and state elections. Kansas’s new dual registration system meant that while he could vote in the presidential race, he had to supply more documents to elect his local representatives.

For Brown, that missing document was his birth certificate, which was in a different state. His case is one of four lawsuits the ACLU filed against Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach, arguing the rule was affecting at least 19,000 Kansans. The ACLU won the case in trial court, and it is now under appeal.

Brown says: “My family has been in Kansas since about 1850. It’s wrong that a bunch of so-called leaders would tell me that I have to show a bunch of extra documents before I can vote. As a military veteran who fought to protect our democracy, it’s particularly offensive.’

The case of course has wide-scale implications. “It just shows how extreme these laws have gotten,” says Dale Ho, director of the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project. “Usually, the way things work is, if there is reason to think you may not be eligible to vote, they say, ‘Maybe we’ll double check.’ But instead, we’re flipping the process around, where we are double-checking everyone, including a 90-year-old World War II veteran. It’s just insane.”

Philanthropic organizations have long funded work on issues such as election integrity, voter access and education. In recent years, many states have passed laws that make it harder to vote – purportedly to reduce fraud, and efforts by the current administration are making voting rights organizations and civil rights groups even more worried. Foundations focused on democratic rights and civic engagement are supporting litigation and advocacy, as well as outreach efforts. But given the current threat to Americans’ right to vote, there seems to be agreement that philanthropy needs to do more.

Carnegie Corporation of New York, Ford Foundation and Open Society Foundations (OSF) are some of the long-term funders of voting rights work. Some say they have stepped up funding of litigation in recent years due to a spate of laws making voting more difficult, as well as a 2013 Supreme Court decision, Shelby County vs. Holder, that gutted major parts of the Voting Rights Act, a landmark 1965 law that helped prevent racial discrimination in voting.

Carnegie Corporation, for example, funds a coalition of ten public interest law firms that work to protect the right to vote, says Geri Mannion, the foundation’s program director of the U.S. Democracy and Special Opportunities Fund.

“Our viewpoint is that we want every citizen to have their voices heard and their votes count,” she says, “especially those who are at a disadvantage.”

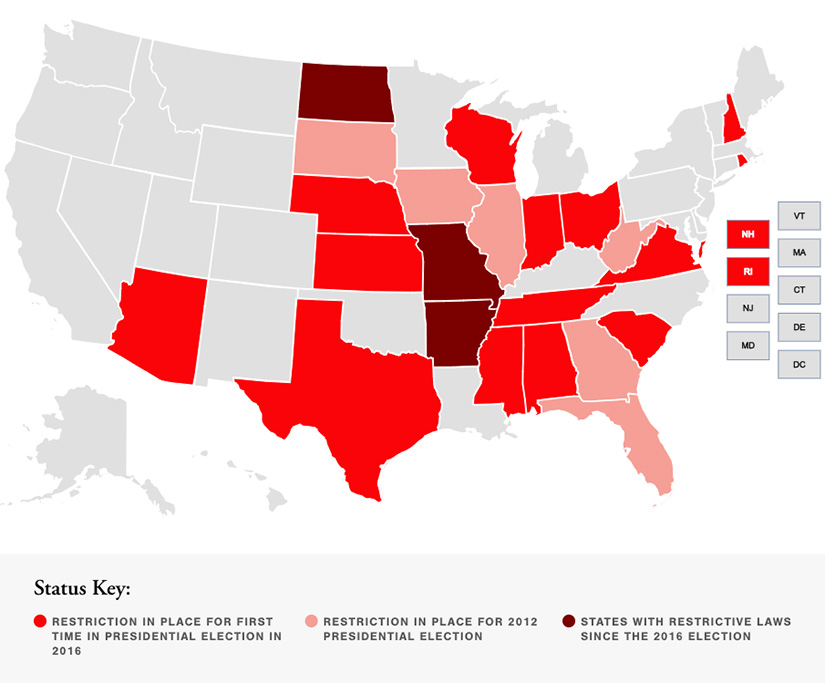

Since the 2010 election, hundreds of measures have made it harder for Americans to exercise their constitutional right to vote. Ten states have put in place burdensome voter ID requirements, seven have made it harder to register to vote, six have cut back on early voting options, and three have made it harder for people with past criminal convictions to vote, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. In 2017, at least 99 bills to restrict access to the ballot have been introduced in 31 states, and five states have enacted laws making it harder to vote.

Voting Restrictions in America

The restrictions often disproportionately burden minorities, low-income individuals, students, and people with disabilities, who may have a harder time accessing and paying for required IDs, reaching Department of Motor Vehicles (DMVs) in remote and rural locations, or getting to far-off polling stations. For example, up to 25 percent of African-Americans lack government-issued ID, compared to only 8 percent of whites.

Other voting restrictions can also have discriminatory effect, such as cutting early voting days, as minorities often rely more on such options. In 2012, black voters in Ohio voted early at twice the rate as whites. In some places, the Sunday before Election Day has historically been the busiest voting day for blacks, thanks to “souls to the polls” events after church. In a legal case in North Carolina, a court said that cutting Sunday voting is equivalent to a “smoking gun” regarding discrimination. Limiting early voting days, imposing voter ID requirements and changing registration requirements target blacks “with almost surgical precision,” the court said.

Julie Fernandes, OSF’s advocacy director for voting rights and democracy, says the 2013 Supreme Court decision Shelby v. Holder opened the doors for such troubling laws. The ruling removed a requirement for states with a history of discriminatory voting practices to get pre-approval for changes in their voting laws by the Department of Justice.

“Now that the protections of Shelby are gone, we’re seeing much more intentional racial discrimination and voter suppression efforts,” she says. “The funders are waking up to that, and saying, ‘This is a real crisis – what are we going to do about it?’”

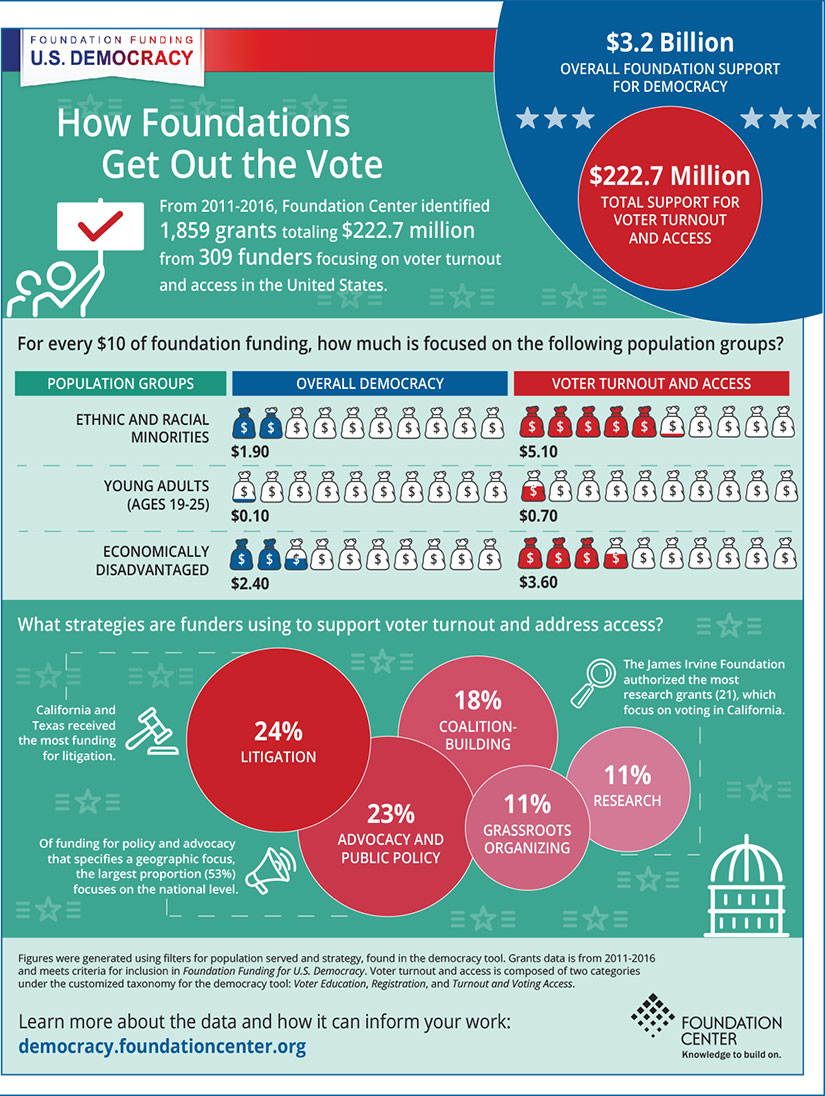

Between 2011 and 2016, 309 funders distributed 1,859 grants totaling more than $222 million for voter turnout and access, according to the Foundation Center. Litigation was the most popular area, followed closely by advocacy and public policy, then coalition building. Some of the key recent successes have come from lawsuits, with courts striking down laws such as Texas’s voter ID and redistricting laws, and North Carolina’s voter ID law. The Supreme Court recently said it will hear a key gerrymandering case, which could influence how electoral district lines are drawn across the country.

Between 2012 and 2016, the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project won or settled 15 cases in 12 states protecting the voting rights of more than five million people, Ho says. Before the election, the project planned to grow from five to seven attorneys, but the current plan is to expand to eleven. Ho says that foundations and individual donors are to thank for that.

Ho and others working on voting rights say the current administration poses a great threat to the right to vote. Under new leadership, the Department of Justice is taking a different side in these court cases. President Trump also appointed a commission on election integrity led by Vice President Mike Pence and Kobach, whom the ACLU calls “the king of voter suppression.” The commission says it aims to tackle voter fraud, but studies have shown voter fraud is almost non-existent, raising concerns about the commission’s intentions, such as purging people from voting rolls. Most states recently refused the commission’s request for voters’ private information, and at least seven federal lawsuits have already been filed against it.

Foundation executives say they are responding by ensuring their grantees have funding that is long-term and flexible, so they can quickly address new developments. For example, when the commission sent its request for information, one of Ford’s grantees, Color of Change, quickly reached out to its members to put pressure on secretaries of state not to comply.

Still, some say there has not been enough support given the threat level. Judith Browne Dianis, executive director of the national office of the Advancement Project, says the civil rights organization has not seen spikes in donations, like Planned Parenthood has seen in light of recent attacks on reproductive rights. Often, foundations increase funding only during election years, but that means many restrictive measures get passed in between, Browne Dianis says.

“That is not how we should be safeguarding democracy,” she says. “Our democracy deserves a continued, vigilant watchdog apparatus. “I think the challenge is to get more funders into this space.”

The Funders’ Committee for Civic Participation, which brings grantmakers together, is seeing more interest from foundations looking to get involved with voting rights and civic engagement, Executive Director Eric Marshall says. Last year, the committee added 16 members – the most in its nearly 35-year history. In the first half of this year, it has already added another 16 members, giving a total of 85.

“While there is increased interest, there is still a tremendous gap that philanthropy can fulfill,” he says, adding foundations should be willing to invest in the long-term fight to protect the right to vote. “Foundations need to think about what interim success looks like and trust organizations with strong track records, follow advice on the ground and trust that even if there is short-term failure, you’ll see success in the long term.”

Browne Dianis says some foundations inaccurately view voting rights work as political. Another challenge is that sometimes, money for voting work competes with dollars for political candidates, she says.

“It’s great if you can fund a great candidate,” she says, “but if the election gets stolen, what’s the point? I think the individual donors miss that. If we don’t get the voting piece right, then Americans won’t be heading to the voting booth.”

One important tool for fair elections is the census, which is done once every 10 years and is scheduled for 2020. The census helps determine everything from legislative districts to congressional apportionment. Because the current administration has been openly anti-immigrant, many funders say they are concerned people in immigrant communities will be afraid to provide census information to the government. A number of foundations have been pooling resources together to fund outreach around the census, ensuring it is conducted fairly and accurately, and that it is adequately staffed and financed.

“There is deliberate intention in the funder community to pay attention to the census given its significance, and to invest resources earlier than has happened in the past,” says Erika Wood, Ford’s program officer for civic engagement and government.

Wood and others say another key area is election administration and modernization, as the election system is underfunded and outdated. Poll workers, including volunteers, are often not well trained, Carnegie Corporation’s Mannion says.

“The fact is that our country talks a lot about democracy, but it really doesn’t put money where its mouth is,” she says. “Imagine running your business on volunteers and the biggest sale day of the year, you rely on them to show up?”

Some philanthropists are funding modernization efforts, while others are focusing on state-based capacity-building, restoring the right to vote for people with past criminal records, or proactively advocating for laws that make voting easier. But regardless of their priorities, foundation executives agree: in a democracy, the right to vote is worth fighting for.

As the late Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall said: ‘Where you see wrong or inequality or injustice, speak out, because this is your country. This is your democracy. Make it. Protect it. Pass it on.’