Where there is a will, there is a way. The U.S. federal government recently announced it will pull out of the landmark Paris agreement, but environmentalist Carl Pope remains hopeful. Cities and states give him hope, he says, as does philanthropy.

“We have a huge coalition of states, cities, private businesses, universities and churches that have said they want to do the right thing,” says Pope, who, along with the former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, authored the book “Climate of Hope.” “Philanthropy now has to shift its vision from how to persuade the federal government, to how do we enable local sectors – whether public or private – to implement changes that will reduce emissions.”

Pope, the former head of environmental organization the Sierra Club and a senior advisor to Bloomberg, says that philanthropy can show why clean energy is not only good for the environment, but is profitable.

“Philanthropy now has to be more in the business of enabling pilot projects to demonstrate how profitable all this is,” he says, “rather than persuading people to make a sacrifice based on the risks if we don’t act.”

There are many examples of how philanthropy has done this, Pope says. In India, U.S. philanthropists partnered with the private sector and the government to encourage production of energy-saving LED lights. Not only did the lights become cheaper as a result, enabling more people to access electricity, but India became a major producer of this technology. The market is the driving force now, he says, “but philanthropy had to prime the pump.”

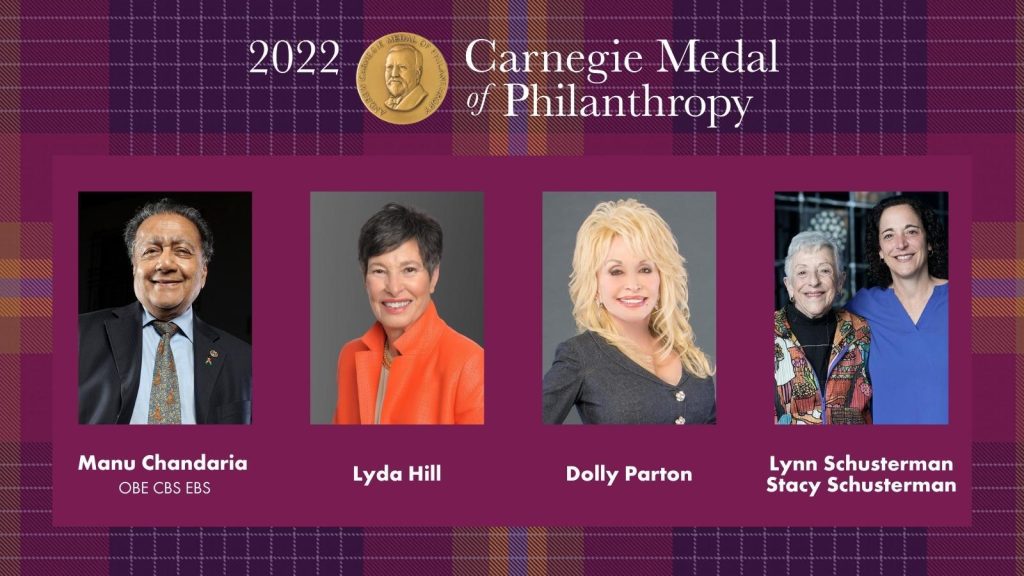

President Trump announced in June that the United States would withdraw from the historic Paris agreement, the world’s commitment to reduce harmful carbon emissions. The same day, Bloomberg pledged $15 million through his foundation to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Bloomberg, a 2009 Carnegie Medal of Philanthropy recipient, has been instrumental in getting others to commit to reducing carbon emissions. The list of more than 1,200 governors, mayors, businesses, investors and universities who have signed up to the We Are Still In open letter supporting the Paris agreement keeps growing.

Pope says that there are countless cities on all sides of the political spectrum taking the lead on clean energy. Houston – the natural gas capital – gets nearly 90 percent of its power from wind and solar energy. Salt Lake City plans to transition to 100% renewable energy sources by 2032, and Portland is committed to 100 percent clean energy by 2050. Even the Kentucky Coal Mining Museum recently announced it was switching to solar power.

Nick Nuttall, a spokesperson and director of communications and outreach for the UNFCCC, says there is a growing need for the UN to work with foundations and the private sector to fight climate change.

“Philanthropy can, by its very nature, sometimes do things and take risks that business itself doesn’t want to take in the absence of certainty, or maybe because of a policy vacuum,” he says. “Philanthropists can also operate in ways which aren’t just brutally financial. They may have other reasons for wanting to support climate change; it may be for social values, or gender, or women’s issues.”

John Coequyt, director of federal and international climate campaigns at the Sierra Club, says philanthropists like Bloomberg, Microsoft Co-founder Paul Allen and Virgin Group’s Richard Branson play a critical role that goes beyond dollars.

“There is definitely an element of actually being advocates for the changes that they want to see, whether that’s divestment on their side, or using their influence to get companies and governments to make decisions,” he says. “These are people who have influence and it’s really important that they use their influence to advance the goals their philanthropy is trying to achieve.”

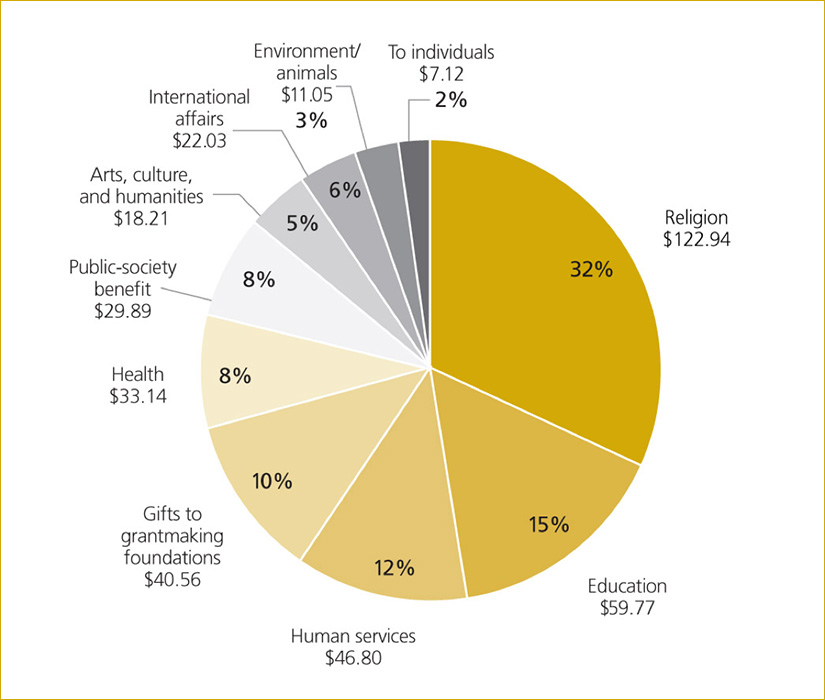

Some philanthropists have been encouraging others to get involved. The presidents of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation – which are among the biggest funders in the climate change field – wrote an op-ed in 2015 urging philanthropists to step up, and pointing out that less than 2 percent of philanthropic dollars go to climate work. Hewlett Foundation President Larry Kramer recently outlined ways philanthropy can do more, such as by supporting nations and networks committed to the Paris agreement, rallying support from business associations, and working with banks and finance ministers to make investing in clean energy easier.

One recent example of a philanthropic effort in this area is Oak Foundation’s six-year, $20 million grant to help communities in Africa and the Arctic adapt to climate change. And in May, MacArthur Foundation announced $19 million to support cleaner and cheaper energy in the United States, bringing the total amount in its Climate Solutions program to $120 million.

Still, the money goes both ways. A 2015 report found U.S. donors gave more than $125 million over three years to spread disinformation about climate change and curtail progress.

It is difficult to say how much is going towards climate change today. But the latest Giving USA report found giving to causes supporting the environment and animals saw the largest increase among the various categories in 2016, at 7.2 percent.

Coequyt, from Sierra Club, says the day the United States announced it was withdrawing from the Paris agreement was the organization’s biggest online fundraising day of the year. But the need remains immense because the current administration may try to rewrite codes that protect everything from water, to air, and endangered species, he says.

“There is definitely need for federal defense and the scale of that is daunting,” he says, “but it is also true that no one should think that because of that attack, there isn’t an ability to make progress on climate change.”