Pathbreaker: Charting Andrew Carnegie’s Life and Legacy in the Hall That He Built

A new exhibition follows the remarkable journey of the young factory boy who used his prodigious gifts to become the most prominent philanthropist of his time

“He’s an enigma,” says Gino Francesconi with both intensity and wonderment. “The more I get to know him, the more elusive he becomes to me.” Francesconi has spent some time getting to know Andrew Carnegie. As archivist and director of the Rose Museum at Carnegie Hall, he has curated Andrew Carnegie: His Life and Legacy, the museum’s first exhibition about the hall’s founder, on display through the end of October 2019 in celebration of the centennial of Andrew Carnegie’s death.

Francesconi has spent his entire career under the roof of one of Carnegie’s greatest cultural contributions, starting off as an usher at Carnegie Hall 45 years ago. “I worked my way down from the balcony,” he jokes, referring to the Rose Museum’s location on the second floor.

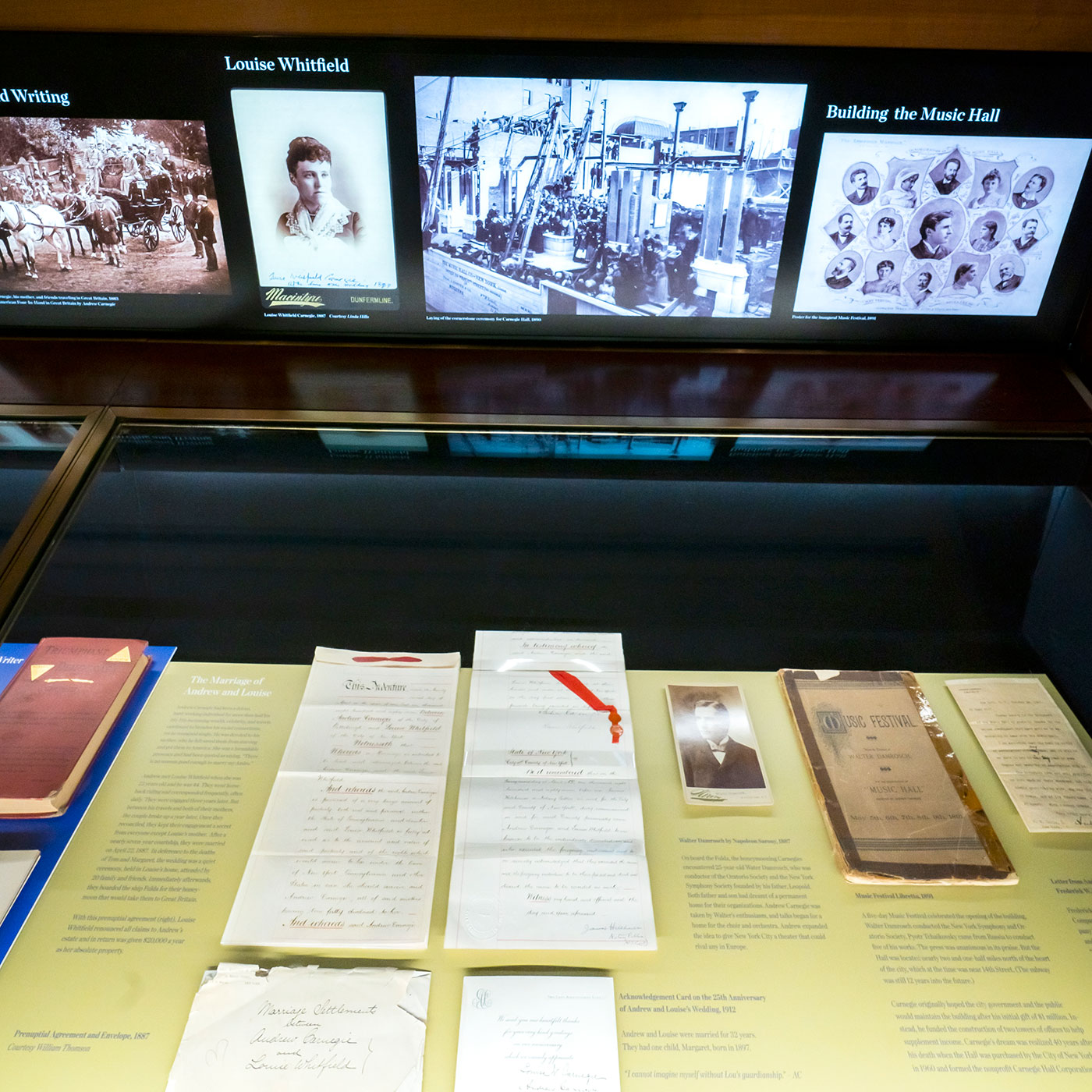

In preparation for the exhibition, Francesconi spent a year researching, interviewing family members, poring over biographies, and digging through archival documents, vintage photographs, and historical artifacts. The resulting display deftly charts Carnegie’s journey from humble beginnings in Dunfermline, Scotland, to his position as the most prominent philanthropist of his time, a story unfolding across two 13-foot exhibition cases in the museum — a tight space for such an extraordinary life.

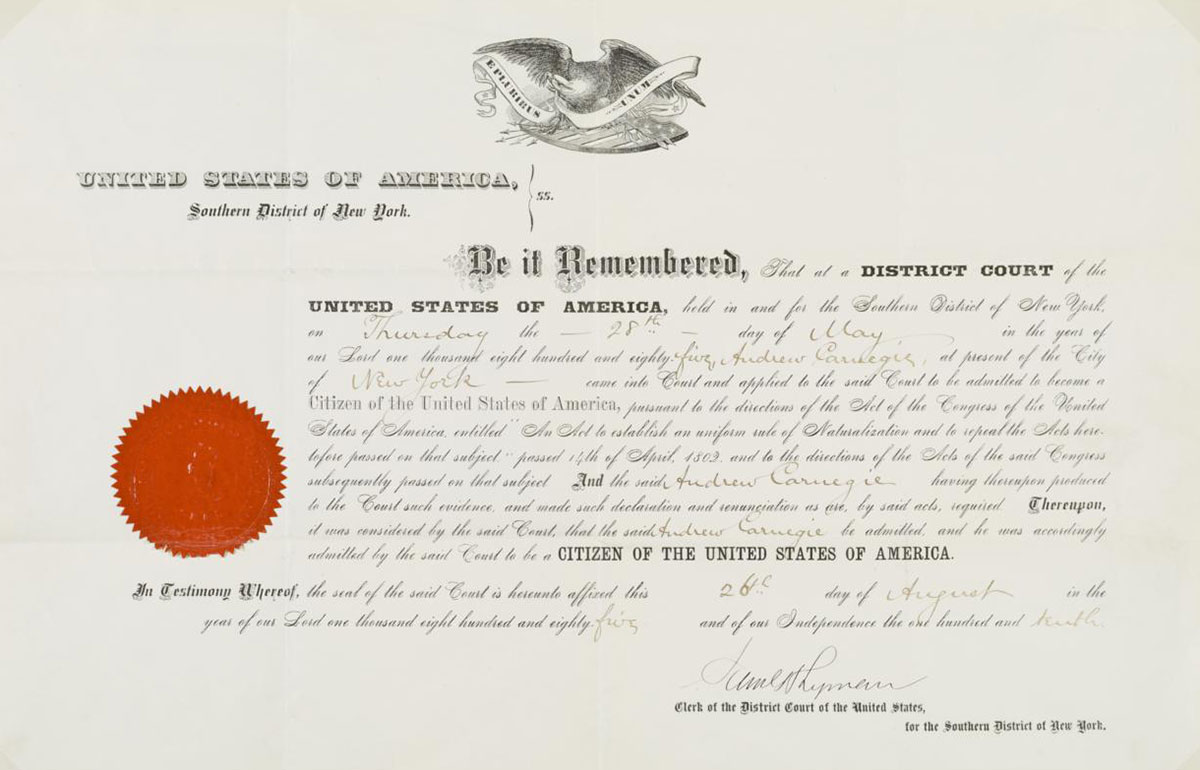

Many parts of Carnegie’s rags-to-riches story hardly seem credible. The early poverty. The grueling 10-week journey, by boat, ferry, and barge, that brought him and his family to western Pennsylvania in 1848 after his father lost his job in Scotland. The 12-hour shifts as a bobbin boy in a Pittsburgh textile factory, earning $1.20 a week to help the family make ends meet. And then … the boy’s ability to quickly master Morse code, making him something of local phenomenon … which led to a promotion … which brought him to the attention of the man who would tip him off to his first investment. To a remarkable degree, Carnegie possessed the ability to make insightful — even visionary — decisions at the critical junctures in his life.

Keen Instincts, Indelible Experiences

Young Carnegie heard about a well-to-do man who possessed a large library that he made available to working boys. He knocked at the door but was turned away when the man learned that he was but a lowly bobbin boy. Feeling deeply that this was wrong, the 13-year-old Carnegie had the acumen to write a letter to the editor of the local newspaper protesting this iniquity. The letter must have helped because the wealthy man changed his mind — and Carnegie went on to educate himself in that very library.

“It’s surprising how keen, from a very young age, his instincts were,” says Francesconi. “His quest for knowledge … his very uncommon sense of common sense!” Not to mention his sense of what is right and just, which would later come to play such a prominent role in his philanthropic work.

“Carnegie was about 20 years down the road about almost everything. He had impeccable timing: to be in the right place at the right time and to know what to do with it.”

— Gino Francesconi, Director, Rose Museum, Carnegie Hall

Carnegie soon took a job at the telegraph company running messages. His boss recommended that he invest in a forerunner of American Express. Carnegie’s mother traveled around gathering money from family, scraping together $500 (the equivalent of $10,000 today) for the investment. It proved a success, forever changing Carnegie’s life. After his first dividend check arrived, “a lightbulb went off,” as Francesconi describes it. Carnegie had the realization that he could earn money by investing it — rather than subjecting himself to the harsh demands of manual labor.

An early investment in railroad sleeper cars earned him his first considerable fortune. Carnegie went on to invest in nearly two dozen companies, and he founded the Keystone Bridge Company, which built the first iron truss bridge across the Mississippi. He purchased iron mills and experimented with the newest technologies for converting iron to steel.

By the age of 33 Carnegie was worth $450,000, or what would be $8 million today, more than he needed to live comfortably for the rest of his life. (And this was before his forays into steel manufacturing.) In the posthumously published Autobiography (1920), he wrote about working in the factory as a boy and his early determination: “I began to learn what poverty meant.” It was “burnt” into his heart that his father had to beg for work: “And then and there came the resolve that I would cure that when I got to be a man.” And cure it he did. Having amassed all the wealth he and his family would ever need by his third decade, Carnegie turned his sights to helping others, and helping others help themselves. The early privations combined with his remarkable instincts developed in him a sensitivity to the needs of others as well as a strong sense of what might best serve the wider community.

Setting the Course for Philanthropy

That year, in 1868, he wrote a letter of intent, a declaration to himself that began to define what would become his philosophy of philanthropy. The memorandum was discovered after his death, and his wife, Louise, allowed copies to be made for the Library of Congress and The New York Public Library. In it Carnegie set forth his ambitions: “Cast aside business forever, except for others.… [and take] a part in public matters, especially those connected with education and improvement of the poorer classes.”

Always a voracious reader on a wide variety of topics, Andrew Carnegie began to write, going on to publish dozens of books, pamphlets, and essays on subjects ranging from socialism, international arbitration, and slavery (which he opposed), to travel, economics, and peace campaigns. “He was always writing, he felt inspired,” says Francesconi, “counting Mark Twain and Booker T. Washington among his friends.” The first of Carnegie’s writings to gain wide readership in both the U.S. and Europe was Triumphant Democracy (1886), a book in which he describes how, in less than a century, the United States had surpassed Great Britain as the world’s great superpower. Calling for the abolition of the British monarchy, Carnegie argues that England should follow the American democratic system as a model.

Having amassed all the wealth he and his family would ever need by his third decade, Carnegie turned his sights to helping others, and helping others help themselves.

In 1889 Carnegie published a pair of articles in the Atlantic, which together have come to be known as The Gospel of Wealth. These two pieces — “Wealth” and “The Best Fields for Philanthropy” — caused a sensation by posing a radical idea: men of means should distribute their wealth during their lifetimes for the betterment of mankind, rather than enjoying lavish lifestyles and bequeathing vast sums to their (male) heirs (wives and daughters should be comfortably provided for). He wrote:

This, then, is held to be the duty of the man of Wealth: First, to set an example of modest, unostentatious living, shunning display or extravagance; to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him; and after doing so to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to administer … in the manner which, in his judgment, is best calculated to produce the most beneficial results for the community — the man of wealth thus becoming the mere agent and trustee for his poorer brethren.

Books had offered Carnegie escape and enlightenment as a boy. As he recalled in his Autobiography, “In this way the windows were opened in the walls of my dungeon through which the light of knowledge streamed in. Every day’s toil and even the long hours of night service were lightened by the book which I carried about with me and read in the intervals that could be snatched from duty.” It is then fitting that his first major public donation was the gift of a public library to his hometown of Dunfermline.

Carnegie the benefactor was quickly becoming Carnegie the celebrity. By 1884 he had donated £5,000 for the Carnegie Baths recreation and health club in Dunfermline, funds for a public library in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, and $50,000 to establish the first medical research laboratory in the U.S., at Bellevue Hospital in New York City.

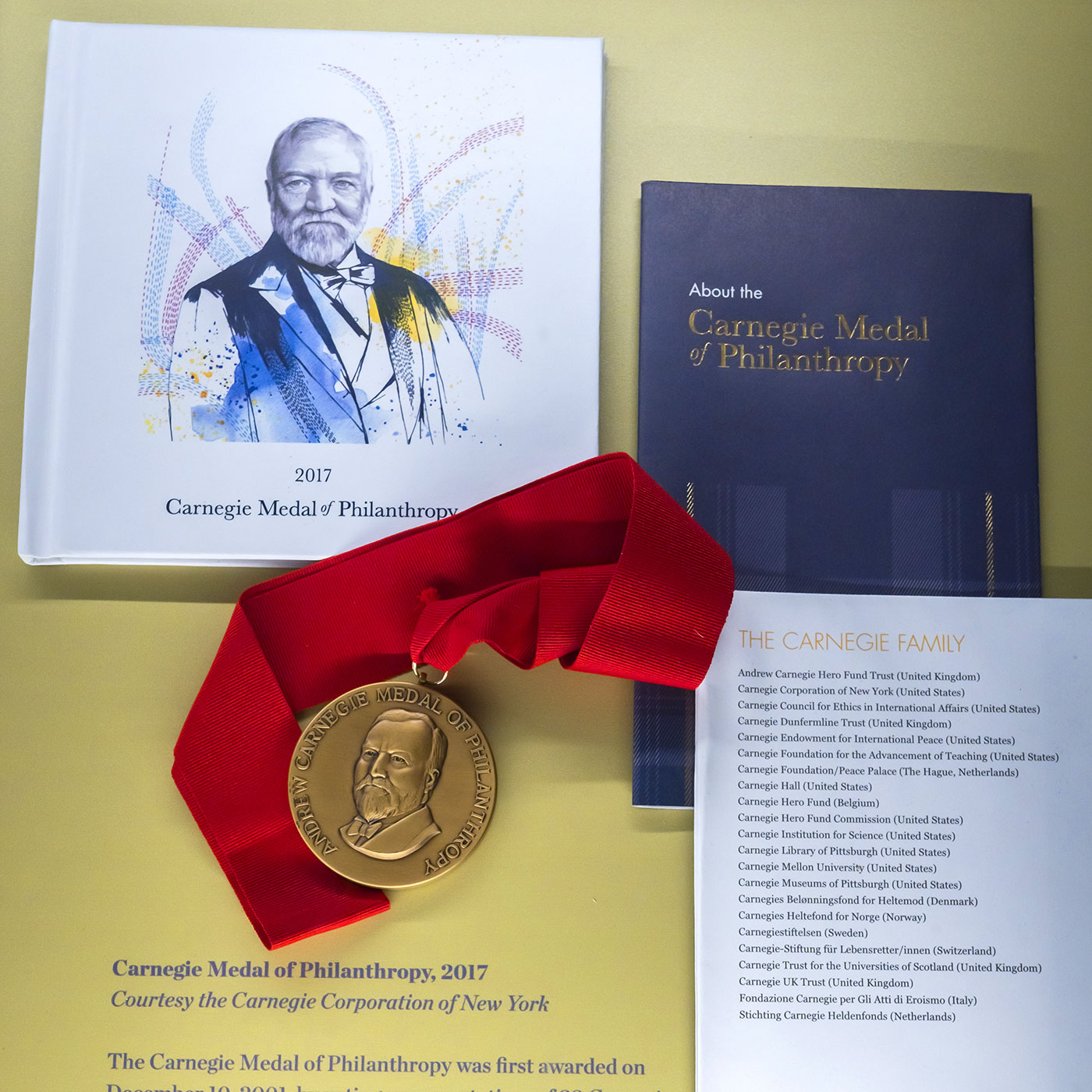

In 1911 Carnegie established Carnegie Corporation of New York to distribute his remaining wealth “to promote the advancement and diffusion of knowledge and understanding among the people of the United States.”

He was a trailblazing philanthropist. “He would give a town a library but wanted them to fundraise for the land,” says Francesconi. “Today that’s called a matching grant; his was the first of its kind. Carnegie was about 20 years down the road about almost everything. He had impeccable timing: to be in the right place at the right time and to know what to do with it.”

One such example was Carnegie Hall itself. At a time when the city was centered around 14th Street, Carnegie looked uptown — to 57th Street. Moreover, while other music halls of the era were built for companies like Steinway or for particular orchestras or impresarios, his was a grander gesture: he built a hall for all of New York City.

“I believe from the moment he started thinking along the lines of giving for the betterment of mankind, he could almost always see the bigger picture,” says Francesconi. “You can almost sense how he thought: Why build just another hall similar to the others when New York City in fact needs something on a larger scale?”

“All good causes may here find a platform,” said Carnegie at the laying of the hall’s cornerstone in 1890. And from its opening day on May 5, 1891, to the present, all causes have indeed found Carnegie Hall a welcoming platform, from a Margaret Sanger talk on birth control in 1917 to one of the earliest appearances of African American jazz musicians on a concert stage. “The variety of events is unique in the world,” observes Francesconi. “No one was ever barred from appearing because of politics, religious beliefs, or race, nor type of music. Nearly 50,000 events have taken place at Carnegie Hall, more than at any other concert hall in the world. I think Andrew would be happy.”

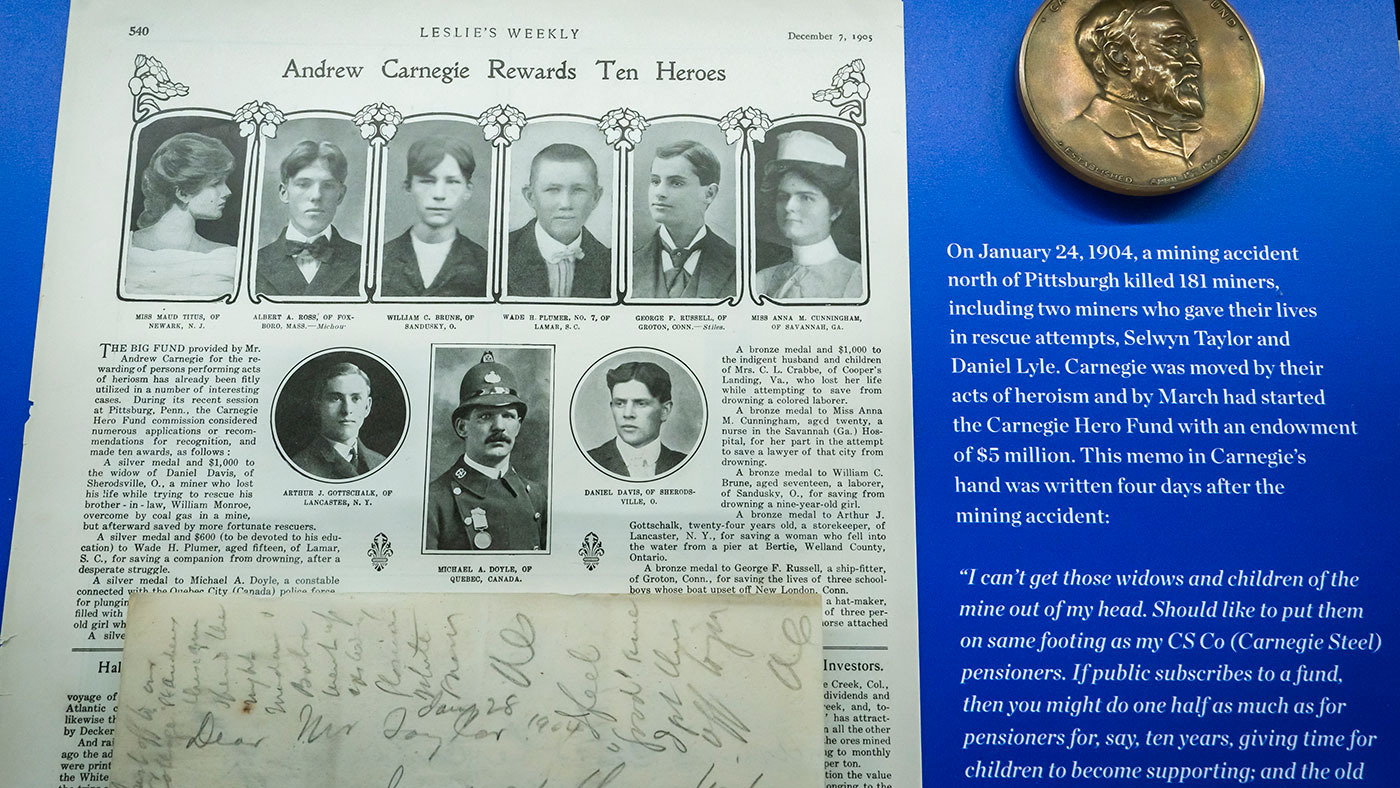

Carnegie gave away more than $350 million during his lifetime — the equivalent of nearly $7 billion today. He built more than 2,500 libraries; donated to the schools that eventually merged to become Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh; and established the Hero Fund to award grants to men and women who risked and sometimes lost their lives for others — to name but a few of many causes, initiatives, and institutions he supported. Carnegie grew increasingly committed to the promotion of world peace in the years preceding World War I: the Peace Palace in The Hague was built thanks to his largesse and he backed an international peace conference held at Carnegie Hall in 1907.

The early privations combined with his remarkable instincts developed in him a sensitivity to the needs of others as well as a strong sense of what might best serve the wider community.

In 1911 Carnegie established Carnegie Corporation of New York to distribute his remaining wealth “to promote the advancement and diffusion of knowledge and understanding among the people of the United States.” He endowed the Corporation with $135 million, giving the trustees permission to adapt its programs to the changing times. He wrote, “Conditions upon the earth inevitably change; hence, no wise man will bind Trustees forever to certain paths, causes or institutions. I declaim any intention of doing so.” This philosophy meant that in the future his foundation would have the freedom to be flexible, for example helping to fund such diverse initiatives as the discovery of insulin and the creation of Sesame Street.

His Carnegie Corporation of New York, the first philanthropic organization of its kind, inspired others that followed, including The Rockefeller Foundation (1913), the Ford Foundation (1936), The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation (1969), and the Giving Pledge (2010).

Gino Francesconi recalls a quotation: “‘Do not go where the path may lead, go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.’” He continues, “If ever a line applied to Andrew Carnegie, that’s it.”