How do you measure good? That is the challenge facing the philanthropic sector. In storybooks it is easy, of course. A fairy waves a magic wand, Snow White smiles. The real world is less straightforward.

Now, help has arrived, in the form of analytical programs that seek to measure impact and bring science to the world of giving. GuideStar Platinum, a platform that allows nonprofit organizations to submit information about their progress and results, celebrated its first birthday in May. More than 2,100 organizations have provided information to date, and the goal is to reach about 10,000 by 2020, says Eva Nico, GuideStar’s director of nonprofit programs.

This additional data is creating more transparency, but measuring impact in the nonprofit sector remains a major challenge, she says. “There is such a broad variety of outcomes that it’s hard to get to a way of assessing impact,” Nico says. “It’s one very small word that stands for many different things.”

GuideStar Platinum tries to answer at least some questions about results. Donors and other players in the philanthropic field are increasingly demanding data on outcomes and impact, and the sector is grappling with how to best collect and use such information.

About 70 percent of organizations using GuideStar Platinum are choosing pre-selected measuring tools to describe their results, while 30 percent rely on custom measures, Nico says. The hope is that over time, it will be possible to determine which measures best define success, so it is easier to see who is performing the best. A long-term goal is to allow users to search by outcome, for example, “graduation rate” for an educational program.

Other platforms and organizations that try to measure impact have also popped up in recent years. ImpactMatters creates “impact audits” to measure nonprofit organizations’ results. Dean Karlan, a Yale economics professor who started the organization in late 2015, says half a dozen audits have been completed so far. The goal is to develop standards that others could mimic, he says.

“There is tremendous demand for data, but it’s a question of focusing it in the right way and creating a clear product that can be systematically applied to lots of organizations,” Karlan says.

Another organization is GiveWell, which conducts in-depth research on programs’ accomplishments and ranks the top charities. But it is limited in scope, as it focuses on a small number of charities. The organization is often cited as an example of “effective altruism,” a movement that encourages people to consider a number of questions and evidence to determine which charities and causes have the greatest impact.

The field of effective altruism is growing, but out of the top 50 donors, only a couple are true effective altruists — Dustin Moskovitz, the Facebook co-founder, and his wife, Cari Tuna, says Stacy Palmer, editor of the Chronicle of Philanthropy.

“I think [effective altruism] is adding rigor to how donors think about things and it’s getting more popular, but I don’t think it’s transformed the way people give,” Palmer says. “It’s forced a lot of people to ask, ‘How do I make sure my money goes the furthest?’ instead of ‘What is it that makes me feel good as a donor?”

Many nonprofit organizations want to produce better data, but lack the funding and trained staff needed to conduct proper evaluations, Palmer says. She adds that some funders are now incorporating this cost into their grants.

Charity watchdog groups say they are aware of donors’ hunger for impact data, but are still trying to figure out best to quantify an often elusive concept. As part of its efforts, Charity Navigator is partnering with others in the field to make available data from 1.5 million digitized tax records filed by nonprofit organizations. The hope is to be able to map and analyze the data, says David Bruce Borenstein, Charity Navigator’s lead data scientist.

“This work is, in one sense, the Rosetta Stone — it allows us to greatly expand our comprehension of how the nonprofit sector ticks,” Borenstein says. “On the other hand, it’s a Pandora’s box, because it opens up the door to profound misinterpretation, misunderstanding and finger-pointing, some of which may be fair and deserved, and some of which may not. It runs the risk of introducing new myths about what makes organizations work and not.”

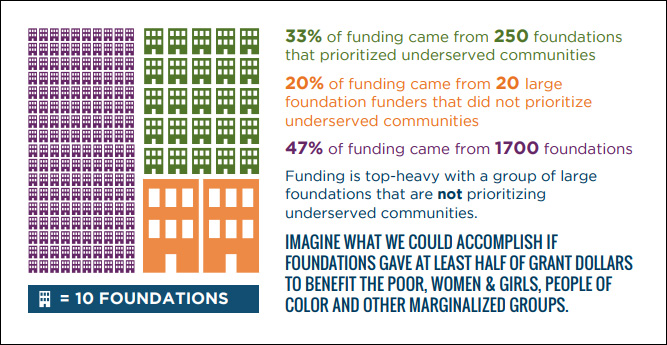

Another challenge is that many foundations and nonprofit organizations remain apprehensive about providing more data. Dan Petegorsky, senior fellow and director of public policy at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, says it is important to distinguish when data is being collected as part of a grant from when it’s being gathered as part of a learning environment.

Petegorsky also says he is concerned about the growing disregard for data in the current political environment. He mentions the recent attitude to reports from the Congressional Budget Office as one example.

“We do have to address the fact that data itself is under attack and being politicized,” he says. “That is something that is certainly a mark of the moment and something that is relatively new for philanthropy to try to take on.”

When it comes to measuring impact, there is no shortage of challenges, but the philanthropic field seems eager to tackle them. The biggest question remains: how do you measure success on issues that may take years, or even decades, to change? Ultimately, however, analysing philanthropic efforts will allow us to target resources more effectively and show those who want to help others what their generosity achieves.