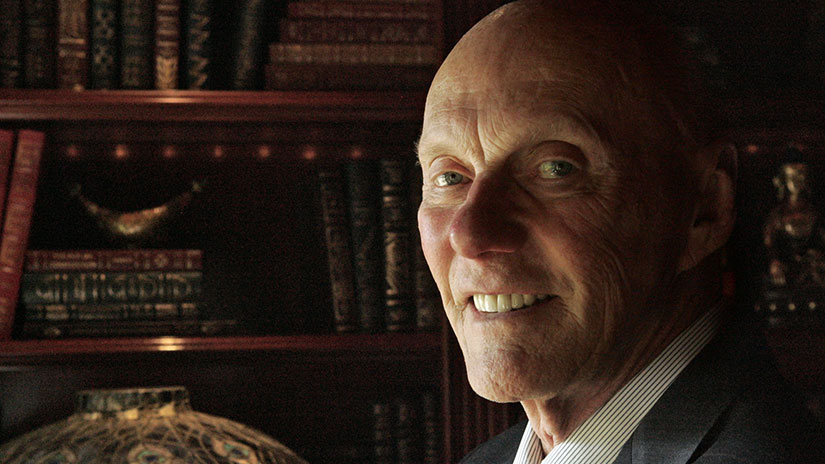

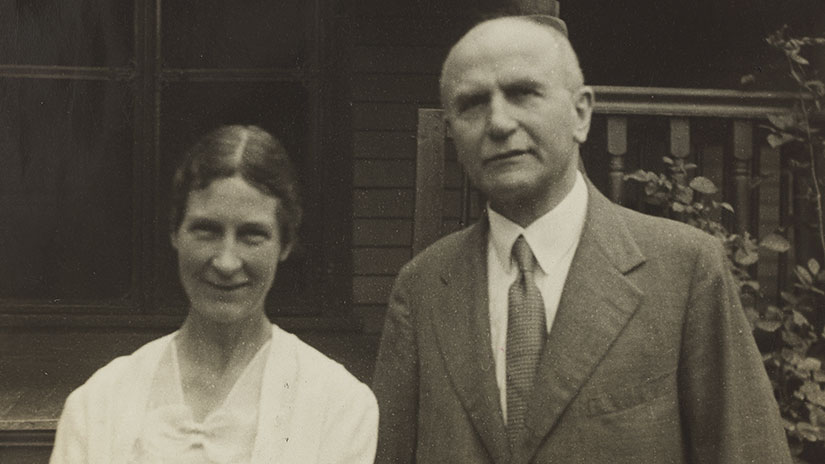

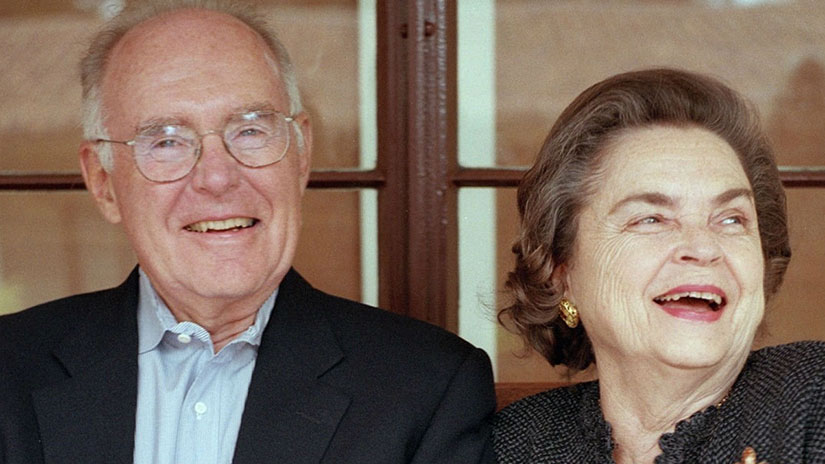

Philanthropy is a relatively young field in terms of innovation (#GivingTuesday, microgiving), but it can trace it roots to ancient traditions. Social entrepreneurship has helped remake the philanthropic landscape in recent years, but many still cite the great religious texts as their reason for giving. Joan and Irwin Jacobs touch upon both the old and the new, embracing the best of philanthropy past and present, and applying themselves with intelligence and passion to the task. They are an extraordinary couple.

Joan and Irwin were both raised in Jewish homes in the Northeast — homes steeped in the tradition of giving, not only as a family matter, but also as a religious duty. The similarity of their backgrounds has helped inform their decision-making as philanthropists. Speaking to the San Diego Union Tribune, Joan said, “Our families were philanthropic, but on a very different level. They gave to the local synagogue, but not in any major way. We both came from very humble homes. We’re very fortunate to be able to do what we’re doing now.”

Early on, each was aware of the Jewish obligation of tzedakah, with memories of placing small coins in a box (called a pushke). Monies collected would go to the synagogue or to another worthy cause. As the Jacobses found greater and greater professional and financial success, the coins and the pushke definitely — so to speak — expanded, and they would eventually sign The Giving Pledge, joining the commitment made by the world’s wealthiest individuals and families to give the majority of their wealth to philanthropy or charitable causes either during their lifetime or in their wills. While their motivations may have been time-honored, the efforts and causes to which Joan and Irwin Jacobs are inspired to contribute are resolutely modern and forward-looking.

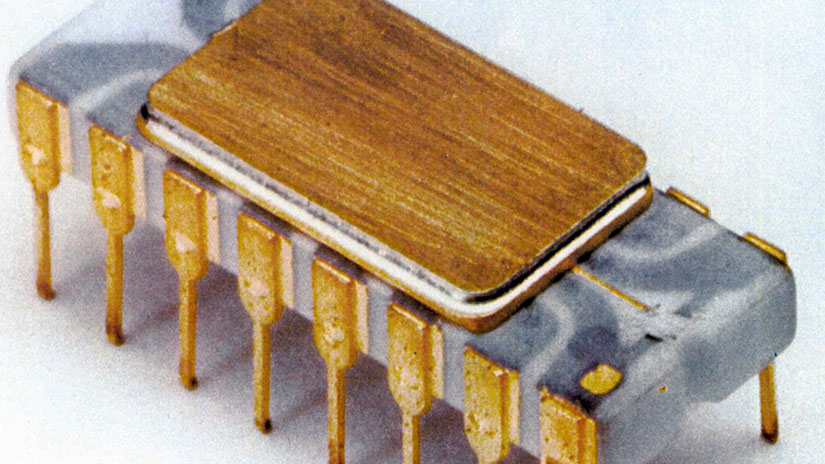

Irwin made his fortune through the technology company Qualcomm, while Joan found success as a dietician. The fields are quite different, but the couple are united in crediting their achievements to the educational opportunities they were afforded — and naturally enough, education became a major part of their giving. Numerous universities have been recipients of their philanthropy, most notably Cornell University: the Jacobs Technion-Cornell Institute, a cornerstone of Cornell Tech’s new campus on New York City’s Roosevelt Island, will create “pioneering leaders and technologies for the digital age.” Clearly, for the Jacobses education and science are top priorities, and they have also given hundreds of millions of dollars to the likes of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of California San Diego, and the Salk Institute (where Irwin served as chairman of the board for a decade).

Moving beyond education and science, the couple has made a name for themselves in San Diego by providing unwavering support for such worthwhile endeavors as the La Jolla Playhouse, the central library, and the San Diego Symphony — this last the beneficiary of a lifesaving infusion of funds. The couple stays involved with the arts locally, science nationally, and education globally — and the aim is to inspire others to follow suit. In their giving, Joan and Irwin Jacobs have continued to live by the Jewish concept of tzedakah, the responsibility to give aid, assistance, and money to worthwhile causes, which they first absorbed as children. The little coin box may have grown immensely, and helped build a building or two or three — or more. But the message remains the same: if you can give a portion of your personal substance to the common good, it is your responsibility to do so. In fact, Judaism teaches that the donors benefit even more than the beneficiaries from tzedakah. An ancient idea, perhaps, but today it seems more relevant than ever.