Giving is part of America’s character, culture, and economy. It is an engine for ingenuity in the United States, and it is part of our nation’s social contract.

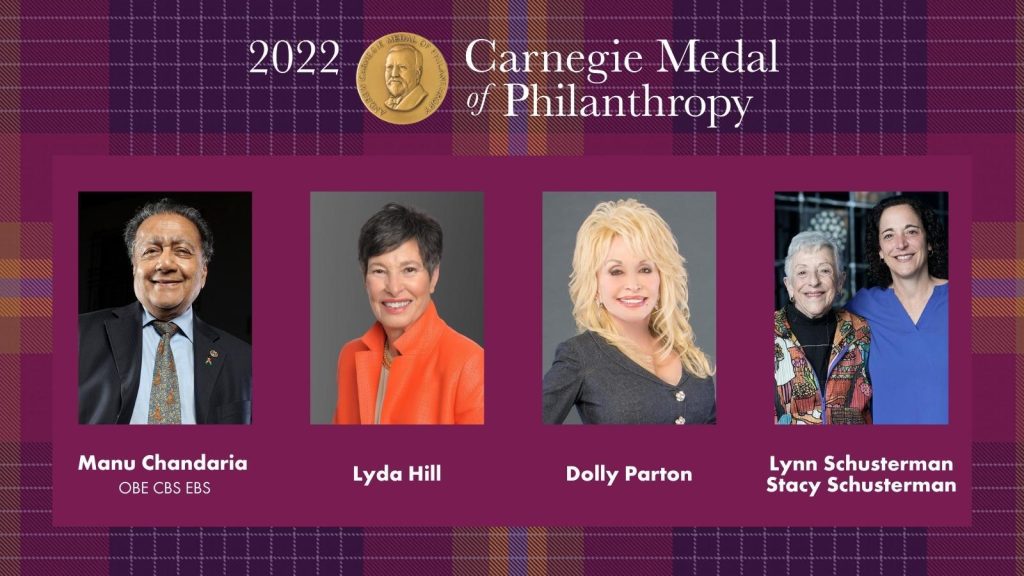

On October 3, 2017, members of the family of Carnegie institutions from Europe, the United Kingdom, and the United States gathered to honor nine remarkable individuals who have followed in the footsteps of our institutions’ founder, Andrew Carnegie. These extraordinary philanthropists, who collectively have donated several billion dollars to a broad swath of worthy causes, received the Carnegie Medal of Philanthropy in a biennial celebration at The New York Public Library. It was the ninth such ceremony the Carnegie institutions have hosted since 2001.

The Carnegie Medal of Philanthropy provides an opportunity to celebrate Carnegie’s own rich philanthropic legacy, as well as his philosophy of giving, outlined in his most celebrated treatise, The Gospel of Wealth. Even though it was published in 1889, more than a century later this essay still serves to remind the world of the importance and prevalence of philanthropy in all our lives. Today, the Carnegie Medal of Philanthropy promotes that same goal.

In the 1830s, decades before Carnegie penned The Gospel of Wealth, the French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville coined the concept of American “exceptionalism” in his classic Democracy in America, in which he marveled that Americans “willingly sacrifice a portion of their time and property” to improve the welfare of their fellow citizens. Since that time, American philanthropy has witnessed many extraordinary acts of generosity. During World War I, for example, humanity witnessed one of the greatest philanthropic acts in history: Americans raised more than $100 million to support Near East Relief in its efforts to save hundreds of thousands of orphans, many of whom lost their families during the Armenian Genocide. The monumental endeavor was hardly an incidental event, however. Rather, it demonstrated the roots, range, and depth of American giving.

In 2016 alone, Americans donated some $390 billion to charitable causes, nearly three quarters of which came not from foundations or corporations, but from individuals hailing from all walks of life.

Today, this generosity of spirit continues. In 2016 alone, Americans donated some $390 billion to charitable causes, nearly three quarters of which came not from foundations or corporations, but from individuals hailing from all walks of life. In addition, the United States also regularly ranks at or near the top of the World Giving Index. These numbers do not take into account the nearly 7.8 billion volunteer hours Americans donate to educational, health, religious, cultural, environmental, and other causes, comprising an array of institutions and ideological views.

It is difficult to find a library, hospital, or school that has not benefitted from philanthropy. These institutions make up America’s flourishing and diverse independent sector, and this diversity is part of what makes our nation so strong. Neither government nor philanthropy can sustain our nation’s nonprofit institutions alone—they must work together to help keep our democracy dynamic and thriving.

The prevalence of partnerships between the public and private sectors is unique to the United States. Unlike many other countries, we do not, for example, have a single federal science ministry or a Department of Culture. Rather, we have a broad array of higher education institutions that are the envy of the world; a range of outstanding orchestras, museums, and theaters; and thousands of social service agencies that provide vital programs to the underprivileged and underserved. It is the generosity of American citizens from all backgrounds that makes the contributions of these institutions possible.

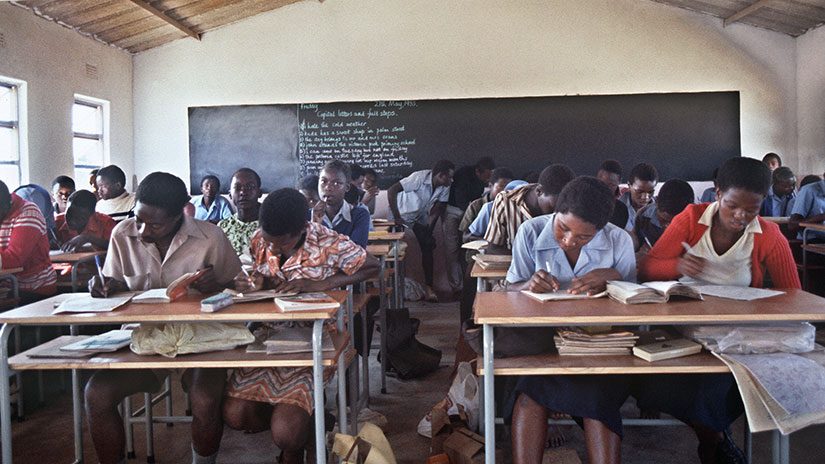

The importance and breadth of public-private partnerships in the United States is perhaps best reflected in our nation’s K–12 education system. It is governed by a patchwork of local, state, and federal bodies, and features an array of schooling options: traditional public schools, charter schools, and private and parochial schools. This system is supported by a broad range of nonprofit education organizations focused on both direct services and reform. Philanthropy, in turn, supports a great number of these institutions’ work. In this way, the philanthropic sector promotes necessary research and innovation for education reform.

Indeed, in partnering with nonprofit agencies, foundations serve as laboratories supporting experimentation for the nation. As the ninth president of Carnegie Corporation of New York, John Gardner, put it, the independent sector is one “in which we are allowed to pursue truth, even if we are going in the wrong direction; allowed to experiment, even if we are bound to fail; to map unknown territory, even if we get lost.”

Of course, the nonprofit world could not exist without favorable public policy, including charitable tax deductions. When Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller originated the concept of “scientific philanthropy” more than a century ago, there were no tax incentives to motivate their generosity. But since their inception, charitable tax deductions have served as a strong driver of giving and a vital source of revenue for much of the independent sector. However, there are those who argue that we should do away with such deductions and that the funds that would otherwise flow to foundations and charitable organizations instead go toward expanding the tax base. Yet removing or reducing the deduction would encourage wealthy individuals to spend more on their families, properties, and idiosyncrasies than on worthy causes. Besides, it is clear that government alone could not support the great array of services the independent sector provides, nor could it maintain the field’s richness and diversity. An independent sector as vibrant as ours can only be sustained by an equally vibrant philanthropic sector. Indeed, philanthropy is the backbone of America’s nonprofit field, which is comprised of some 1.5 million organizations that account for 10 percent of all private sector employment nationwide.

Giving is, in short, part of America’s character, culture, and economy. It is an engine for ingenuity in the United States, and it is part of our nation’s social contract.

Religion is not, of course, the only motivating factor for generosity. Enlightenment ideals—humanism and democratic principles—are also common driving forces, as are social obligations to one’s community, one’s nation, and humanity at large.

My colleagues and friends from abroad are awed by American philanthropy. They often ask me what makes Americans so generous. I give them two answers. For one, more than 75 percent of the population identifies as religious, and every Abrahamic faith, whether Judaism, Christianity, or Islam, demands that the faithful be charitable, that they support the poor, the sick, and the disadvantaged. This is reflected in the fact that today more than 30 percent of giving goes to religious organizations and causes. But religion is not, of course, the only motivating factor for generosity. Enlightenment ideals—humanism and democratic principles—are also common driving forces, as are social obligations to one’s community, one’s nation, and humanity at large.

We often fixate on givers’ motivations, but for me what counts most is the act and impact of giving. In our age of cynicism, I am often reminded of Machiavelli, who scandalized many of his contemporaries with his famous political treatise The Prince. In it, the Prince is only interested in the maintenance of law and order and the stability of the realm, not in his subjects’ motivations for obeying the law. He also holds that leaders should be judged above all by their actions, not their beliefs. This remains true today. Whether givers are driven by guilt, redemption, patriotism, religion, self-glory, hypocrisy—all of this is secondary. The fundamental concern is that no one is obligated to give, but so many do. While we cannot always know a philanthropist’s true motivations, we can always measure the outcomes of their giving.

Of course, the giving industry should welcome such questions and scrutiny because, as in every other sector, philanthropy is not immune to excesses and malfeasance. For example, in some instances, donors dive into addressing very complex problems, such as education, the environment, or poverty reduction, with very little expertise in the field and without seeking expert assistance. They also sometimes attach so many conditions to their gifts that they distract or distort an institution and its mission. This is common in the research field, where donors sometimes provide support on the condition that the research produces a predetermined outcome. Finally, some fear that philanthropists and foundations lack accountability to the public, acting, in effect, as unelected officials supervised only by state attorneys general.

In the face of potential abuses, it is fundamental that the philanthropic sector heed three core principles: transparency, accountability, and responsibility.

In the face of potential abuses, it is fundamental that the philanthropic sector heed three core principles: transparency, accountability, and responsibility.

Carnegie Corporation of New York—one of the oldest foundations in the United States and the first to publish an annual report—has always ascribed to these values. Indeed, more than 60 years ago, the Corporation’s board chairman, Russell Leffingwell, coined the term “glass pockets” at a congressional hearing. Later John Gardner expanded on the policy, saying, “A foundation should practice full disclosure. The larger it is, the more energetically it should disseminate full information on its activities.” The Corporation has long understood, as Carnegie did, that the public has granted us the right to exist, and we therefore owe it to the public to be as accountable and open as possible regarding our activities and funding decisions.

Fortunately, we have a healthy free press that can take to task those who misuse their powers, as well as strong democratic institutions to prevent abuses of trust. As president, Thomas Jefferson famously despised newspapers, but he nonetheless allowed that “the only security of all is in a free press.” (If he were alive today, I believe he would say the only security of all is in a free and well-informed press.)

For those who would criticize philanthropy and philanthropists, I caution that it is always easier to fall into disillusionment and cynicism. It is more difficult and, indeed, more courageous—to stand up for and live by one’s ideals. Like the hundreds of thousands of other men and women who donate their time, talents, or personal funds to worthy causes, the more than 50 recipients of the Carnegie Medal of Philanthropy understand this. They are exemplars of the act and art of giving, demonstrating that generosity is an act of human solidarity. They come from different backgrounds and support different fields, but they all know, as Andrew Carnegie knew, that one’s legacy is not measured by wealth, but by the good one has done for the world. They are, in my opinion, all driven by a common goal: to serve humanity and to make their communities and the world safer and more just for all.

Vartan Gregorian is president of Carnegie Corporation of New York.