FORGING THE FUTURE

Andrew Carnegie’s Transatlantic Legacy

Tackling the Most Consequential Threats to International Peace Through Strategic Insight and Innovative Ideas

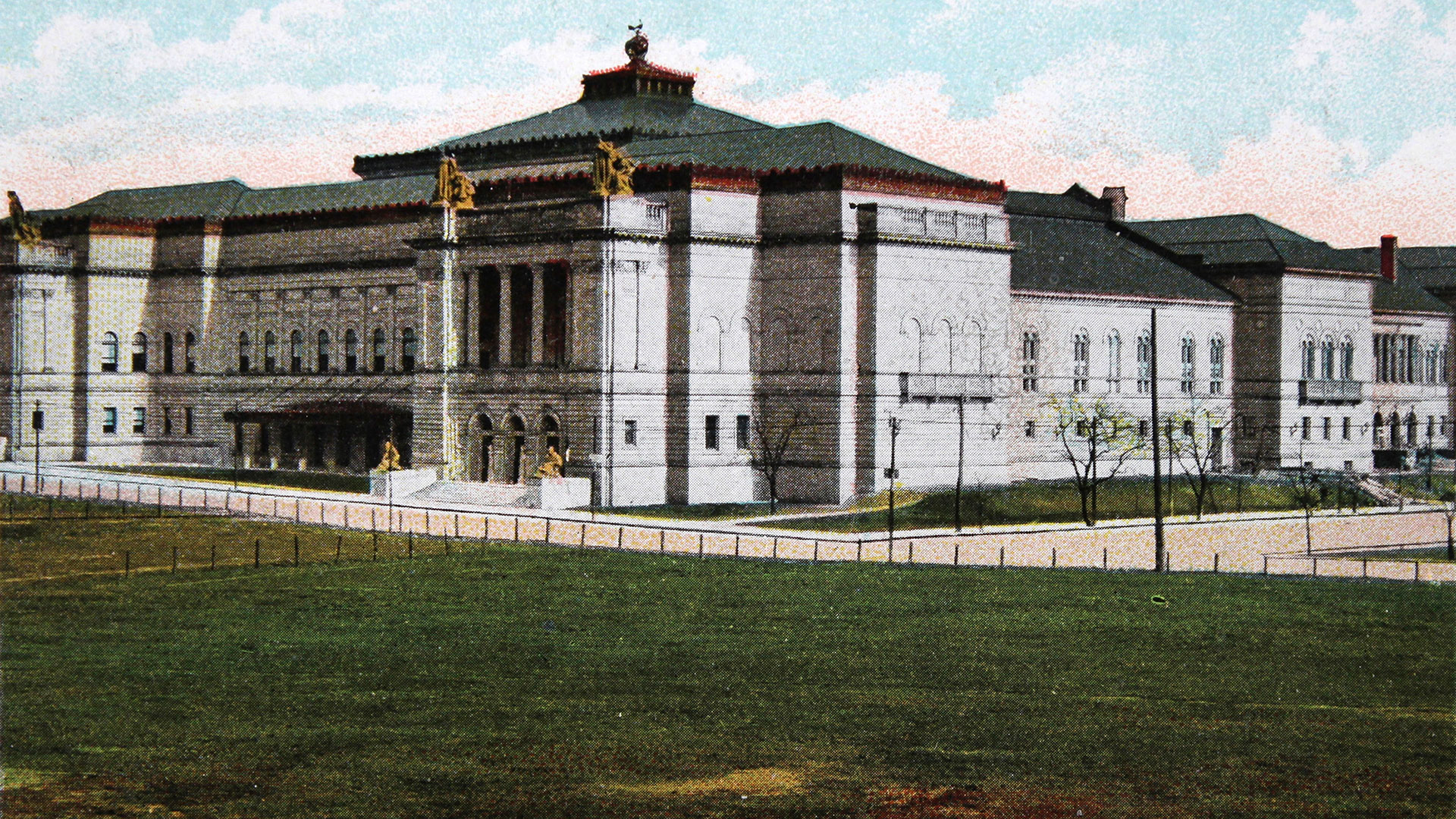

In 1910, driven by a bold mission to “hasten the abolition of international war,” Andrew Carnegie bestowed $10 million toward the creation of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, in Washington, D.C.

Though the world has undergone radical change since then, the organization’s central mission remains unchanged: the advancement of international cooperation to promote world peace through policy research conducted in collaboration with leaders from government, business, and civil society.

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has had 10 presidents since its inception, all of whom have cultivated the organization’s three guiding principles: a commitment to rigorous policy research, a steady focus on effecting concrete global change, and a capacity to respond nimbly to shifting geopolitical currents.

Today, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace employs a growing roster of more than 100 foreign-policy experts based in 20 cities worldwide — from Beijing to Brussels to Beirut.

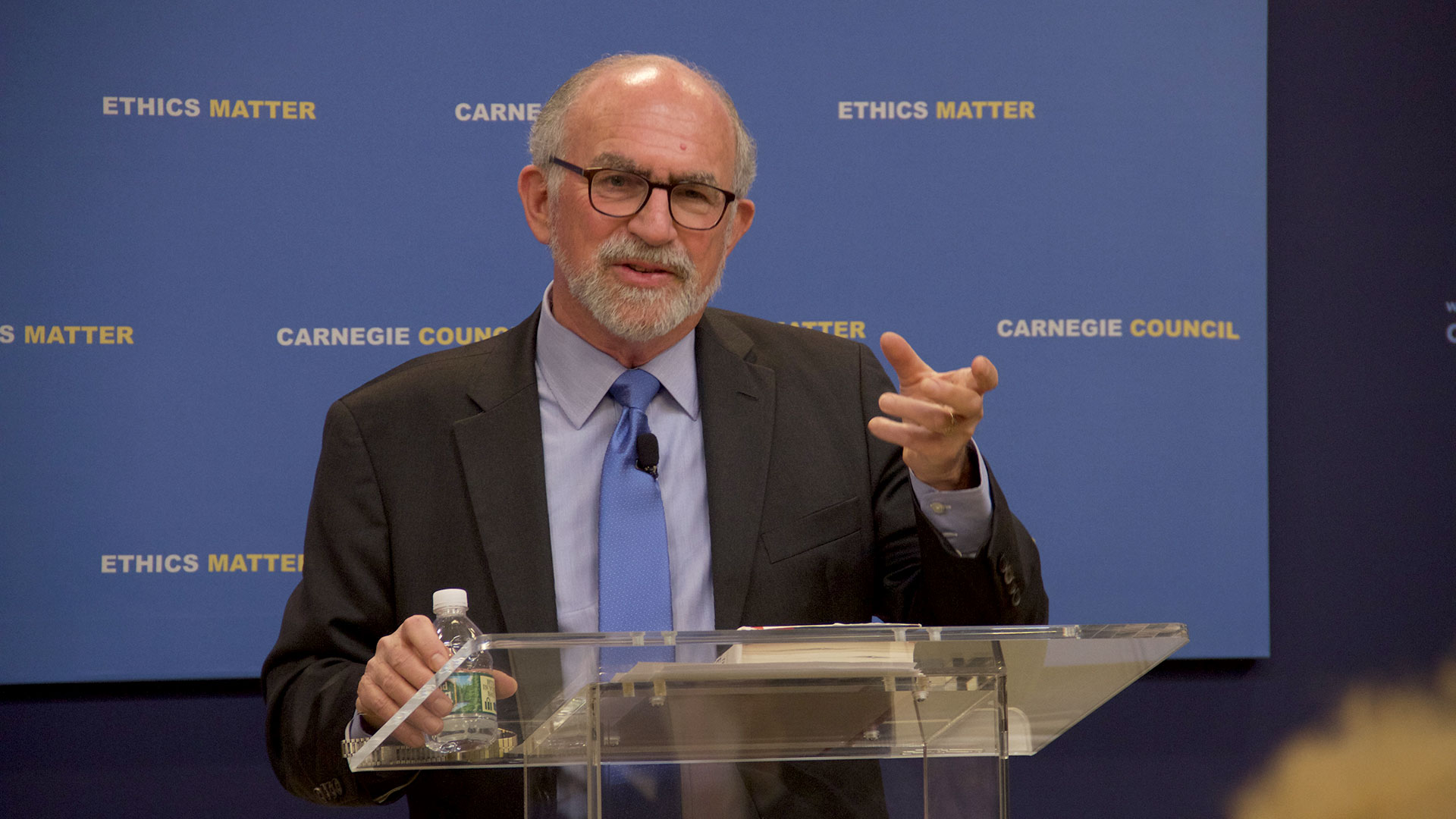

Though the organization continues to expand globally, it still operates under its central mission. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace President William J. Burns states, “In an increasingly crowded, chaotic, and contested world and marketplace of ideas, we offer global, independent, and strategic insight and innovative ideas to solve the most consequential threats to international peace.”

Carnegie Europe, founded in 2007 and based in Brussels, focuses on European foreign-policy analysis. Its scholars conduct research and make recommendations around such fraught issues as the future of EU-Iran relations, the implications of Brexit for the future of Europe, and the challenges posed by shifting military alliances.

In the last few months alone, the organization has brought together experts on Turkey with key representatives of several EU institutions to coordinate the 28-member bloc’s policy towards Ankara regarding migration, visa-free travel, and accession to the EU. And, earlier this year, a senior representative from the German government sought out the organization’s assistance in addressing disagreements on issues like free movement and migration, which have threatened to divide the EU in recent years.

“The strength of Andrew Carnegie’s heritage is as important now as ever,” says Carnegie Europe Director Tomáš Valášek. “Day to day, leading global political figures turn to us to help resolve some of the most pressing problems.”

Andrew Carnegie’s central abiding commitment to pacifism informs all of Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s foreign-policy efforts, guided by an impressive array of experts and policymakers who have earned the institute global renown.

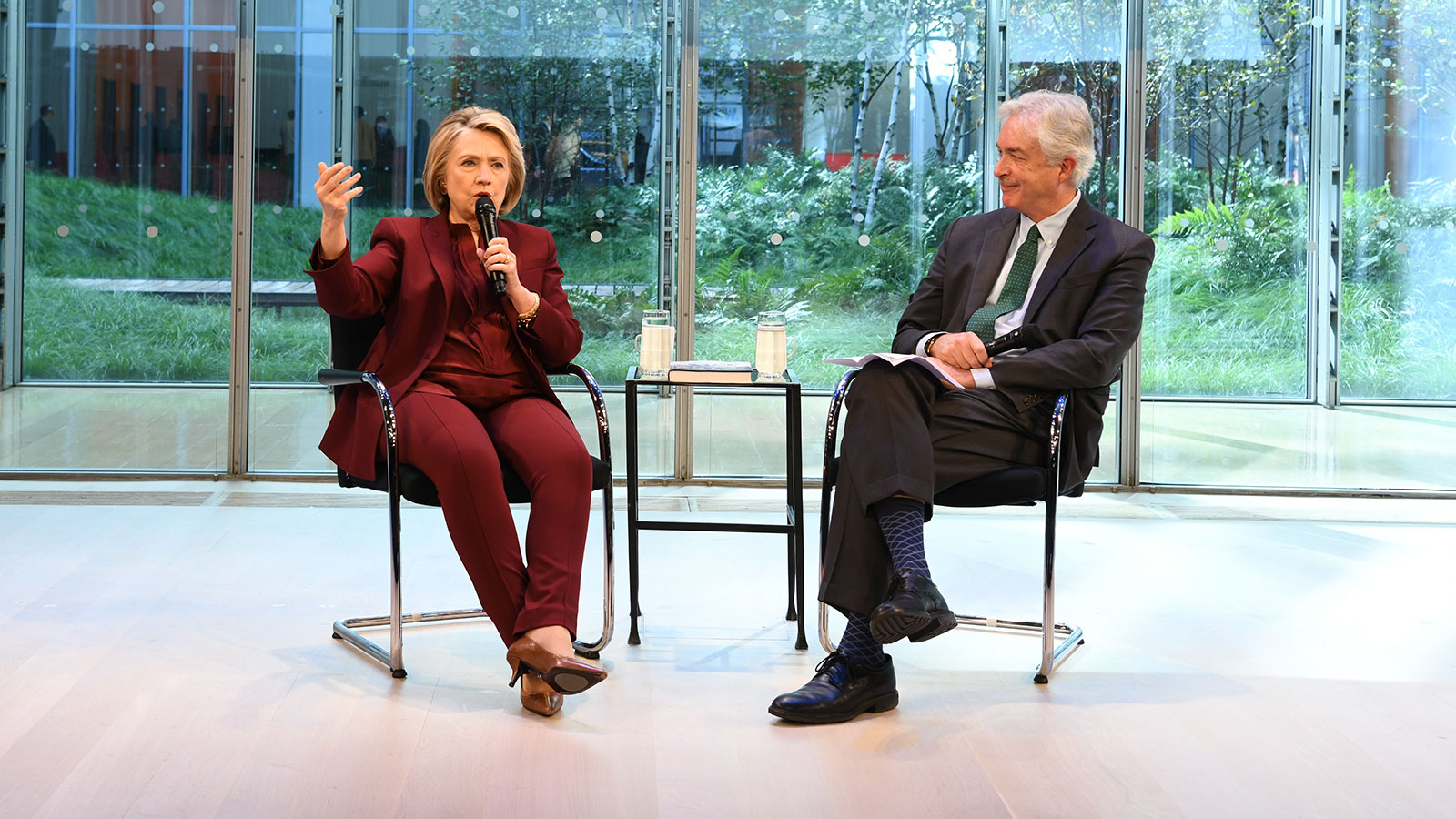

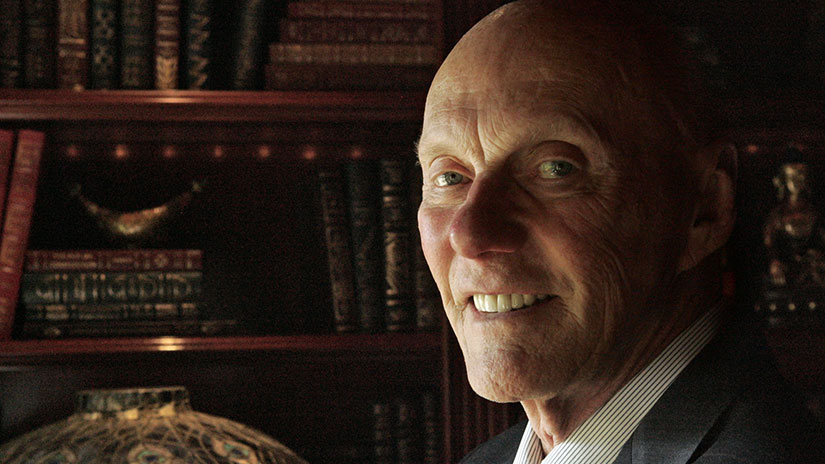

In March of this year, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace announced the election of Robert Zoellick, former president of the World Bank and former U.S. trade representative, to its board of trustees. And in 2017, former U.S. secretary of state John Kerry was named visiting distinguished statesman.

Andrew Carnegie was prone to saying, “Aim for the highest.” Aiming for world peace is indeed a lofty objective. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace continues Carnegie’s core mission, seeking collaboration, understanding, and engagement to prevent war and enhance prospects for global concord.