Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs

Joel H. Rosenthal

President

Letters to Andrew Carnegie | Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs

Dear Mr. Carnegie,

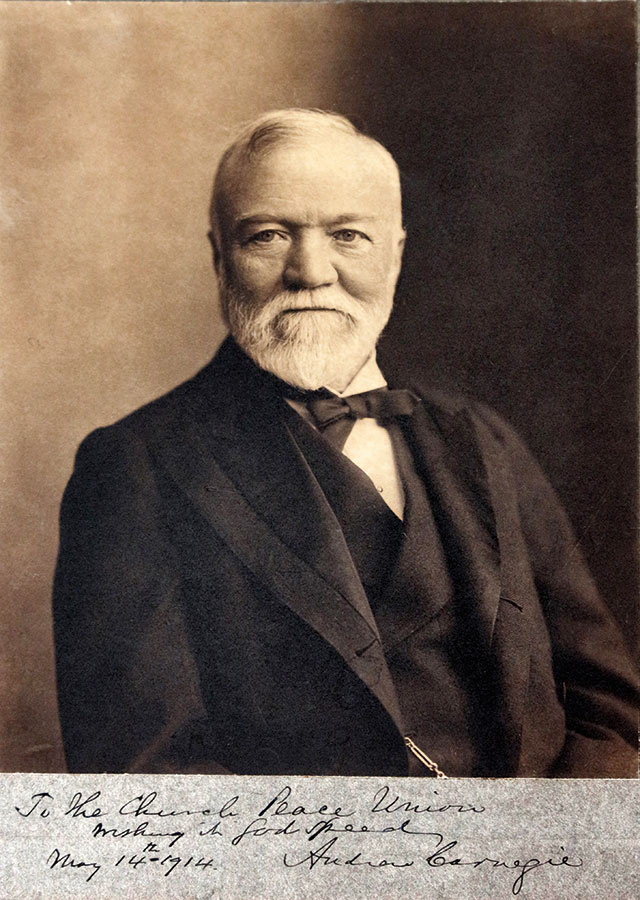

As the current president of the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, it is my privilege to report to you on the eve of the 100th anniversary of our founding.

It is not often that we have an opportunity to think in terms of 100 years. It’s a span well-suited to remind us that while our lives are time-bound, our connections endure. And as much as things change, they remain the same.

Looking back in a personal way, I can see and feel your world of 1914. I can imagine my grandfather, soon to be a telegraph officer in the U.S. Army, his tour of duty awaiting him in France. Today, I find myself wondering if his Morse code was really much different than our texts and Twitter — all dots and dashes turned into hashtags and pixels. Looking forward, I can almost visualize our successors in 2114. I suspect that whatever technology they use to communicate 100 years from now, it will be both simple and astounding — in some ways familiar enough for us to understand, and in other ways astonishing. As much as things change, they remain the same.

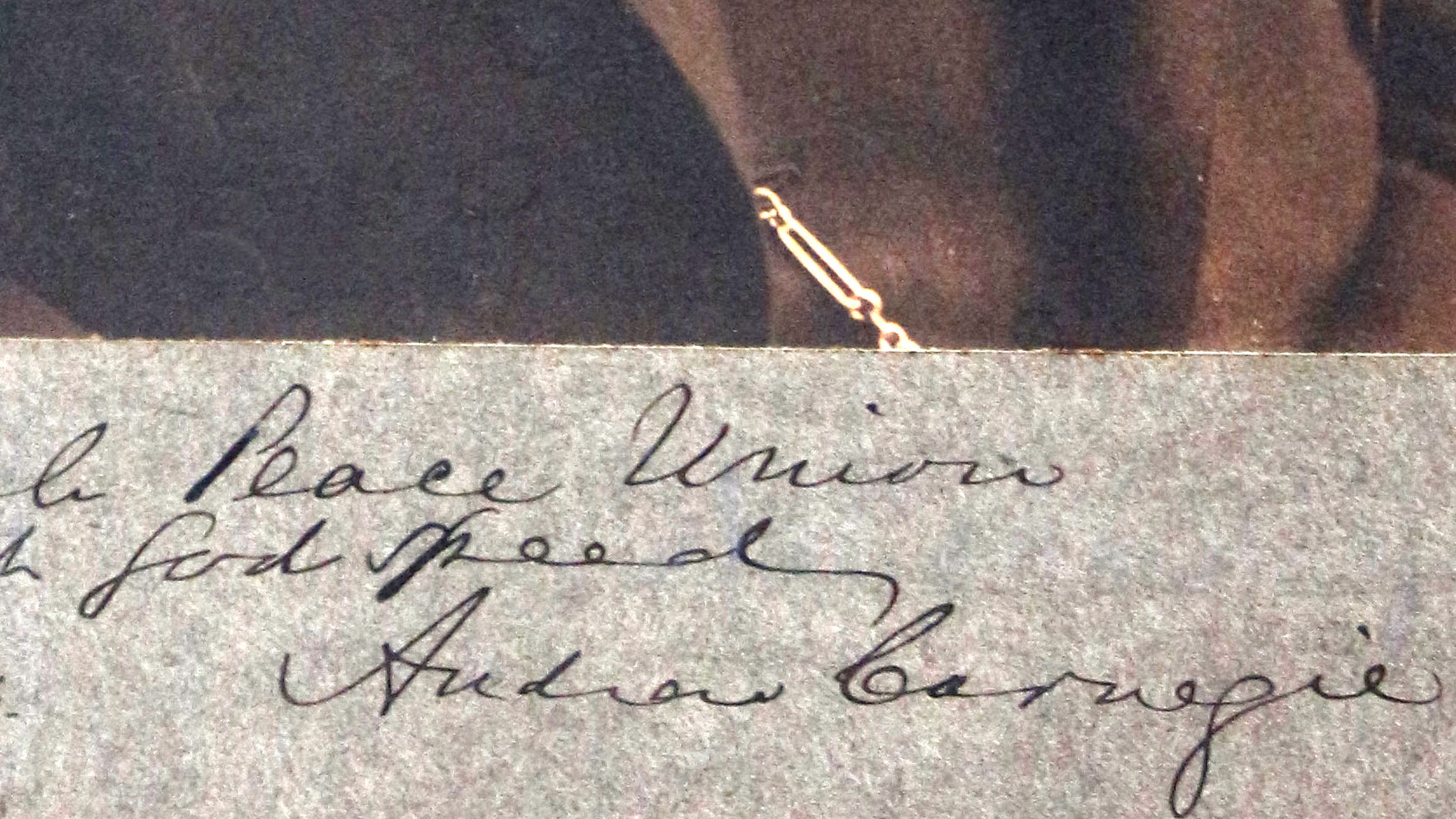

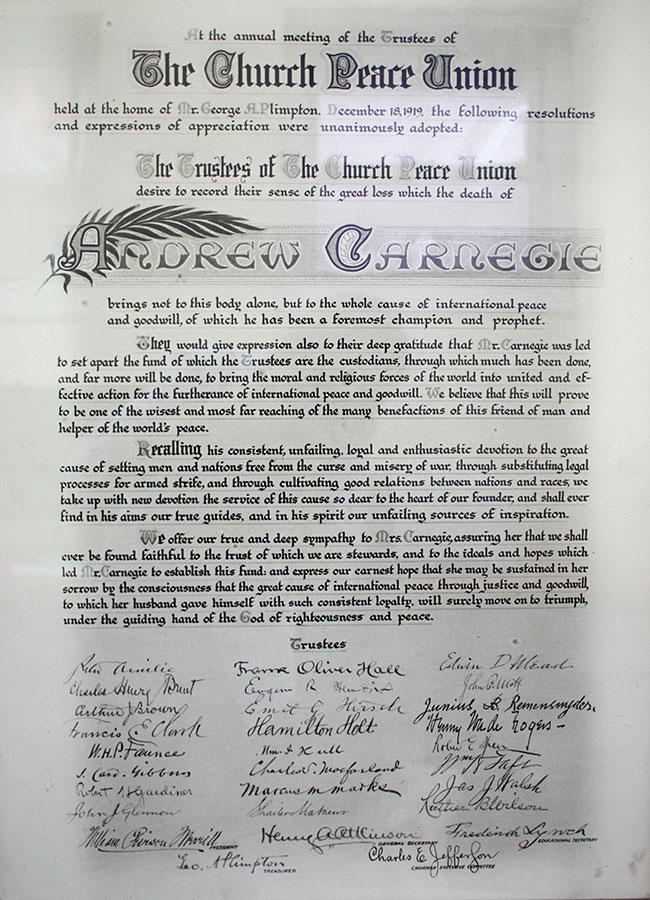

Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs remains proud to be the youngest of your endowments — the last one you established. We remember you created us with urgency just prior to the outbreak of the war. As I understand it, your animating idea for yet another Carnegie initiative was the belief that politics was not just the business of institution building, it was also the business of moral transformation. It was not enough to build the Peace Palace at The Hague and to lobby kaisers, kings, tsars, and presidents to establish the League of Nations and World Court. Peaceful resolution of conflict would depend on changing patterns of behavior, and this change would depend,

ultimately, on moral arguments and educational efforts in favor of peace.

The challenge for us today, as it was at the time of our founding, is to use our moral traditions to help us imagine a better future. Today’s Carnegie Council focuses on the one central question that preoccupied you and your colleagues at our founding: How can we learn to live together peacefully while acknowledging our deepest differences?

The history of the past 100 years shows that in your assessment of world politics, you got some things right, others wrong. This is the all-important background upon which our Council has tried to make its mark on the world. Let’s start with what you got right.

As you demonstrated with all of your philanthropy, it is indeed possible to change the way people think. It is indeed possible to change what is considered moral, just, and right. Legitimacy rests on sentiment and judgment. Legitimacy is, ultimately, a matter of human decision.

You were perhaps most right about the stubborn nature of militarism. We know now that the glorification of war in 1914 led to “the trenches, the mud, the rats, the typhus, and the general futility of World War I” [a quote from Nicholson Baker’s essay, “Why I’m a Pacifist”] and the wars that followed. It is only with tragic irony today that we quote the poet’s Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori — how sweet and right it is to die for one’s country. Even the bitterness of World War I did not stem the numerous twentieth-century slaughters that followed. And yet, despite all of the blood spilled, can we say that the glorification of war has receded?

You were also right about the corrosive effects of imperialism. Your offer to pay $20 million to purchase the Philippine Islands in order to insure their independence was a gesture as heartfelt as it was dramatic. As you said at the time, it is neither natural nor morally right for powerful nations to rule over the less powerful. Empire saps the dignity of both the rulers and the ruled. The past 100 years show that empire bears its share of responsibility for the sorry record of rivalry and conflict in the twentieth century. Many of the political struggles we see today, particularly in the Middle East, can be traced directly to the redrawing of maps in 1919. Economic struggle — especially the persistence of vast global economic inequality — also must be considered in this light.

You were right about the centrality of self-determination and minority rights as keystones to living in a peaceful world. In a world of divided communities, peace depends on pluralism. Pluralism demands institutional arrangements that allow people to live deeply rooted in their communities and yet peaceably with outsiders. Post-World War II Europe has provided a positive example of what is possible. As we see in Scotland today, pluralism is evolving as a peaceful and invigorating concept. But of course this is not so in many other places around the world where pluralism is indeed failing miserably. Over the past 100 years we have learned we should not underestimate the possibilities and the limits of pluralism.

Finally, you were right about the stubborn nature of religion as a formative element in both war and peace. Religion has surely played its role in conflicts — sometimes exacerbated by leaders who have self-righteously and cynically used religious ideology and moral rhetoric to pursue their interests. Yet religiously inspired voices have also been central to the promotion of human dignity and social justice. In either case, we live in a world today that is still often defined according to religious principles in contest.

Let’s turn for a moment to what you got wrong. You were wrong about the simple allure of peace — the assumption that citizens and leaders will inevitably value peace as the highest good. As Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, said recently when asked for a comment on the use of chemical weapons in Syria: “War is obviously terrible, but it’s not the ultimate evil. Some things are worse, and one is the deliberate slaughter of civilians.” Or as Barack Obama put it in his Nobel Lecture, “Evil does exist in the world. A nonviolent movement could not have halted Hitler’s armies. Negotiations cannot convince al Qaeda’s leaders to lay down their arms. To say that force may sometimes be necessary is not a call to cynicism — it is recognition of history; the imperfections of man, and the limits of reason.”

In this vein, you were also wrong about the presumed strength of law as the ultimate trump to power politics. Law depends on both reason and reciprocity, two qualities not always in great supply, especially in extreme situations. The force of reason rarely trumps the imperatives of necessity, realpolitik, ideology, or national mythologies.

You were wrong to assume that international institutions like the League of Nations could temper the heat of national ambitions and shape cold calculations of national interests. For all the moderating influences of international institutions, the Great Powers would never respond faithfully to distant, faceless, unaccountable bureaucracies. Rather, the Great Powers would tend to use such organizations as instruments of power — as a means rather than an end to international politics. As many American secretaries of state have said in commenting upon the United Nations, our approach is “together where we can, alone where we must.”

Finally, you were wrong about the inevitability of social progress. What your biographers have called your cockeyed optimism fed your liberal illusion that peace was merely a technical matter — something that could be engineered by societies that were becoming ever more civilized with the passing of time. Your favorite saying, “All is well since all grows better,” may have reflected your personal experience. But today we have to face the fact that we live in a split world. There are haves and have-nots, those who live in zones of peace while others live in zones of conflict. For those of us in the privileged world, things are indeed good. For at least two billion of our brothers and sisters in poor and unstable areas, things are not so good, and there is no presumption of good times ahead.

For all you got wrong, however, there is an undeniable opportunity we have to build on your legacy to shape the future and to work for positive change. And this is what I would like to focus on in this last section of my report. As you demonstrated with all of your philanthropy, it is indeed possible to change the way people think. It is indeed possible to change what is considered moral, just, and right. Legitimacy rests on sentiment and judgment. Legitimacy is, ultimately, a matter of human decision.

You were persistent in pointing out that civilized nations abandoned practices like slavery and dueling. Surely, you thought, the practice of war — the killing of man by man — would follow into extinction. You would be pleased to know that Steven Pinker wrote a book last year (The Better Angels of Our Nature) arguing that while war is still too much with us, the world is indeed a less violent place than it was 100 years ago. Following your line of thought, he argued that this trend toward a less violent world is inextricably bound to a shift in ethics — a shift in what is considered expected and required behavior.

We have learned over the past 100 years that ethics matter. And here is where our Council has tried to do its part. Ethics, as we practice it, goes beyond moral assertion to entertain competing moral claims. For us, ethics invites moral argument rather than moral assertion. Ethical inquiry enables us to include all moral arguments, religious and secular. It gives equal moral voice to all while giving us the tools to think for ourselves and stand our ground accordingly.

We like to think of our approach today as a sort of enlightened realism — a realism that enables us to understand our own values and interests in light of the values and interests of others. This approach demands the humility to abandon any hint of a crusading spirit and a genuine commitment to try to understand the point of view of others. This is the intent and purpose of our Centennial project, built on hard-won lessons of historical experience, pluralist and pragmatic in nature.

Thanks to the rapid expansion and advances of communications technology, it is now possible for the Carnegie Council to encourage a multi-directional global conversation. Our Studio and Global Ethics Network ventures leverage advances in digital media in service of the enduring values that have guided the Council through its history. We convene, publish, and broadcast programs that reach hundreds of thousands of people around the world. We believe we are honoring your intention to imagine a better future — together with our viewers, listeners, and readers — through education and advocacy for ethics.

None of this is done alone. The value of an institution like Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs is its ability to transmit values over time and space through the lives of the people it touches. So the work continues. We have been very lucky in friendship — especially in the relationships we have developed around the world. I trust that 100 years from now, our successors will have such strong voices for ethics at their side to keep alive the idea that peace is indeed worth fighting for.

Sincerely,

Joel H. Rosenthal

President

This talk, given in 2014 at the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh, at the Carnegie Council Centennial Symposium entitled “From World War to a Global Ethic,” inspired this collection of letters to Andrew Carnegie on the centenary of his death.

Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh

Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland

Carnegie Institution for Science

Carnegie Foundation | Peace Palace

Carnegie Dunfermline Trust | Carnegie Hero Fund Trust

Carnegie Rescuers Foundation (Switzerland)

Fondazione Carnegie per gli Atti di Eroismo

Stichting Carnegie Heldenfonds

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Carnegie Corporation of New York