(Not) Going Dutch

The competition to design the new Peace Palace in The Hague was not without controversy, not least because on May 11, 1906, the jury announced that the winner was … French!

By Fred A. Bernstein

The magnificent Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands, built thanks to the largesse of Andrew Carnegie, soars as testament to the American philanthropist’s unshakable belief that for the progress of mankind, the tide had turned at last, and that “even the smallest further step taken in any peaceful direction would soon lead to successive steps thereafter.”

Big philanthropic initiatives on peace and security have become few and far between, according to a recent article in the Nation, ruefully titled “You Never Give Me Your Money.” Carnegie Corporation of New York’s Stephen Del Rosso told the Nation that he has seen a “retraction of funding” over the course of the past 20 years in the area of peace and security, adding, “It’s lonely out here.” But Carnegie Corporation of New York has peacebuilding in its DNA: its programs build on Andrew Carnegie’s efforts to banish war, which he called “the earth’s most revolting spectacle.” Perhaps Andrew Carnegie’s most tangible such effort was building a home in The Hague for the Permanent Court of Arbitration, an intergovernmental organization created in 1899. “At last there is no excuse for war,” Carnegie said of the court in a 1905 speech to the students at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. “A tribunal is now at hand to judge wisely and deliver righteous judgment between nations.”

Carnegie Corporation of New York has peacebuilding in its DNA: its programs build on Andrew Carnegie’s efforts to banish war, which he called “the earth’s most revolting spectacle.”

In 1913 Carnegie spoke at the dedication of the Peace Palace, the structure designed as the permanent home for the Court of Arbitration. Financed by Carnegie, it “became the physical manifestation of his desire to bring about world peace, the same desire that fuels the Corporation’s work today,” says Del Rosso, program director for international peace and security at the Corporation. Indeed, the Palace now accommodates not only the arbitration court but also the International Court of Justice (the principal judicial arm of the United Nations, commonly known as the World Court), as well as an international law academy and a research library holding the world’s largest collection of materials on international peace and justice.

To ensure that the building would be as lofty as its mission, the planners held an architectural competition — a tradition dating back at least to 1419, when Filippo Brunelleschi was selected to design the dome of the famed Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. By the 20th century, architectural competitions had become de rigueur for significant public projects. The Peace Palace competition presaged several better-known contests: in 1948, Eero Saarinen’s design for the Gateway Arch, on the St. Louis waterfront, was chosen from among 172 entries (including one submitted by his father, Eliel Saarinen). And in 1957, Jørn Utzon, a young Danish architect, triumphed in a competition to design the Sydney Opera House, known for its iconic, sail-like roofs. Tellingly, the Florence cathedral, the Gateway Arch, and the Sydney Opera House are among the world’s most recognizable structures.

At their best, competitions elicit compelling designs, often from little-known architects who wouldn’t otherwise have been considered for such high-profile commissions. To the list of relatively obscure architects who have won important competitions, add the name Louis-Marie Cordonnier (1854–1940) of Lille, France, whose Peace Palace design was selected in 1906 from among 216 entries. More than a century after its completion, the red-brick and sandstone building stands as an “icon of the development of international law,” in the words of Arthur Eyffinger, author of the definitive study The Peace Palace: Residence for Justice, Domicile of Learning (1988). It is also a major tourist draw. Upon entering the building, visitors immediately sense that it “is a ‘palace’ in the true sense of the word. The distinguished impression of the building’s exterior is heightened still by the soberness, the quiet of the interior, which has no room for ‘overcrowding.’ … Even a layman could guess at once that choicest materials from all corners of the earth have been gathered and lovingly made into what they are by artists’ hands,” wrote C. H. de Boer, author of a guidebook to the Palace (1948; 1951).

Such extravagance was made possible by the deep pockets of Andrew Carnegie, whose fondest hope was that the work conducted within the Palace walls would make war obsolete. This aim was shared by Russia’s Czar Nicholas II, who in 1899 convened the Hague Convention to address the problem of international weapons proliferation. Although the 26 nations participating in the meeting failed to reach a significant arms agreement, they did succeed in founding the Permanent Court of Arbitration as a means of resolving future international disputes.

Because the court had no home of its own, in 1900 Russian diplomat Frederic de Martens traveled to Berlin to enlist the aid of the U.S. ambassador to Germany, Andrew Dickson White, in securing funding for an appropriate structure. White immediately thought of Carnegie, whose interest in world peace was well established. Initially, the philanthropist offered to donate a library to the new court, but after protracted negotiations he pledged $1.5 million (more than $43 million in today’s dollars) toward construction. In 1904 the board of the Carnegie Foundation, which is based in The Hague, assumed control of the project, and a year later the Dutch government bought the Foundation two properties, totaling 16 acres, in an idyllic spot alongside the extensive royal woods known as the Zorgvliet. The Foundation, advised by a leading Dutch architect, began planning the competition.

Every architecture competition involves trade-offs, and this one was no exception. As Eyffinger, a classicist, law historian, and former head librarian of the International Court of Justice, recently explained in an email: “Prize competitions are highly interesting, if mostly saddening stories in which, more often than not, human nature and rivalry prevail over technical and strictly professional issues.” However, the ultimate success of the Peace Palace design speaks highly of the process followed by the Carnegie Foundation.

The first thing the organizers of an architectural contest must decide is whether to allow all architects, or only a preselected group, to enter. An open call may bring a flood of submissions, but few from established architects (who are likely to be deterred by the low odds of winning). Conversely, an “invited competition” would exclude lesser-known architects who might have the most original ideas. In the case of the Peace Palace, an additional question arose: Should the competition be limited to Dutch architects, as the Royal Institute of Dutch Architects demanded at the time, or should it be open to architects of any nationality, the view — not insignificantly — of Andrew Carnegie himself?

Eventually, the Carnegie Foundation board decided on a competition that was both open and closed. It would be international — as befits an organization dedicated to world unity — but limited to entrants nominated by the 26 countries that took part in the 1899 Hague Convention. (The single exception was the nomination of American architects, which was left to Carnegie himself; he chose Peabody & Stearns of Boston and Carrère & Hastings of New York.) The Foundation board, besieged by requests from foreign architects and their professional associations that the competition be open to anyone, eventually relented, although only the invited firms were paid a stipend for participating.

Another issue in architecture competitions is whether to solicit fully developed designs or mere conceptual sketches. The former approach, requiring hundreds of hours of work, might discourage all but the best-funded practitioners. The latter, a so-called ideas competition, may result in the choice of an exciting scheme by an architect who then turns out to have little practical experience.

In this case, the board set the bar very high: the “Programme of the Competition for the Architectural Plan of the Peace Palace for the Use of the Permanent Court of Arbitration with a Library,” distributed worldwide on August 15, 1905, informed architects that they had seven months to produce plans, elevations, sections, and perspectives for a finished structure meeting hundreds of precise requirements. The process proved overwhelming, and, as the deadline approached, the participating architects were granted an extra month.

More than 200 entries arrived by the (revised) deadline, April 15, 1906. The six jurors (chosen by the Carnegie Foundation board) included the president-elect of the Royal Institute of British Architects, the architect of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and the German emperor’s personal architect, among other grandees of the profession. The one American was William Robert Ware of Milton, Massachusetts, founder of the architecture school at Columbia University.

Altogether, the entries comprised more than 3,000 drawings — so many it was hard to find a place to hang them, until Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands offered the walls of her Kneuterdijk Palace. There, in May, after reviewing the proposals privately, the jurors convened to pick a winner. They began by naming their favorite projects. Forty-four plans received at least one nod, and thus qualified for further discussion. The field was eventually narrowed to 16. Several jurors were unsatisfied with the pool of entries and suggested, to no avail, that the contest be reopened.

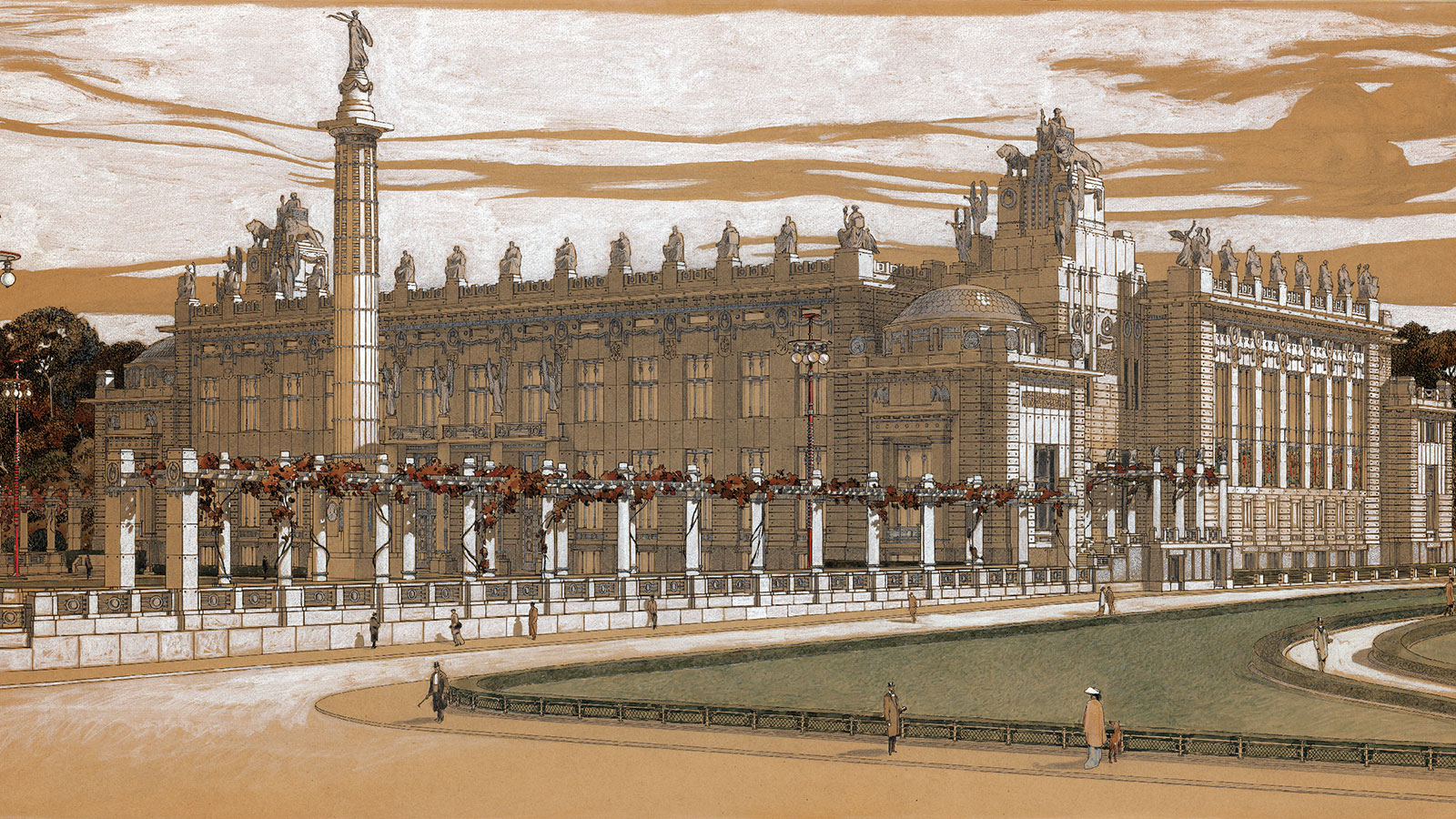

The jury took a final vote on May 11. In first place was Cordonnier’s scheme for separate courthouse and library buildings connected by a corridor, with four large corner towers, all in a richly decorated, neo-Renaissance mien. The jury, in a written statement, praised the design for “following the local traditions of XVI Century architecture.” But Eyffinger succinctly notes that this was not the case. “Cordonnier’s design,” he writes, “was in no way linked to Dutch tradition.” Nor did the choice of period make sense to everyone. “Why on earth the 16th-century style?” one critic asked mockingly. “Is it because Holland was engaged in war (with Spain) most of that period?” (In a detailed critique of the completed palace, the New York Times would later peg the style “Sicilian Romanesque,” explaining that the design reflected “in some degree both the Norman and the Oriental influence resultant from the many political mutations of the island of the Mediterranean in the Middle Ages.”)

More positive attention was focused on the fourth-place design, by the Austrian architect Otto Wagner, a leader of the Vienna Secession movement and one of the great figures of 20th-century architecture. In fifth place was the New York firm of Greenley & Olin, whose design hued to the neoclassical style exemplified by The New York Public Library’s central building at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street. A plan by another highly influential architect, Eliel Saarinen of Finland, didn’t make the top six, nor did any proposal from the Netherlands. Modernism was also nowhere to be seen among the finalists.

The selected plan prompted not just criticism but also litigation. Between 1907 and 1911 a group headed by Hendrik Berlage, a celebrated Dutch architect, fought to annul the result of the competition, claiming, among other things, that the cost of Cordonnier’s scheme would far surpass the announced budget. Although the board ultimately won dismissal of the suit, at one point it seriously considered scrapping the jury’s verdict and going with the Saarinen plan. Not legally bound by the jury’s decision, it also at one point thought of moving forward with the Greenley & Olin proposal.

Make It New — But Not Modern

When the Peace Palace opened in 1913, the critic for the New York Times christened its throwback architectural style “Sicilian Romanesque,” going on to note that many of its graceful but often inappropriately “warlike” details were of a nature to provoke criticism from “the lovers of pure art.”

The Peace Palace was meant to embody the promise of the future. But its style was based entirely on the past. Indeed, oddly for a building dedicated to eradicating war, many of its details were derived from forts and castles. Its architect, Louis-Marie Cordonnier, was accustomed to replicating the work of earlier eras. Born in 1854, he studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he was influenced by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, restorer of France’s medieval monuments, and Charles Garnier, architect of Paris’s ornate opera house. But the design of the Peace Palace was backward-looking even within the context of Cordonnier’s career, given its unmistakable resemblance to his Dunkirk (France) Town Hall, completed in 1901. Perhaps it’s understandable that Cordonnier would reuse aspects of past projects — the Peace Palace competition required architects to assemble detailed drawings in a very short time and on a tight budget. (As one of the 26 architects invited to participate in the competition, Cordonnier would have been paid a small fee.) Moreover, the Beaux-Arts tradition encouraged copying the successful elements of older buildings.

But what about the judges? Were they right to pick a design that eschewed innovation, perhaps believing that historical references would give the building gravitas and, thus, legitimacy? Greenley & Olin’s admittedly beautiful and for its time thoroughly “safe” neoclassical design would have fit that bill nicely. Or would they have done better to choose something more forward-looking, given Andrew Carnegie’s desire that the world break with its past?

The New York Times weighed in on September 7, 1913, with an entire page devoted to the new Peace Palace. And though the sub-headline was kind (“It is a superb structure, the interior being especially beautiful”) the article itself was not. It stated:

The Palace of Peace … is far from being such a representative specimen of modern architecture as would have seemed fitting to its object. Indeed, it is wholly imitative of the architecture of another age, without the slightest effort at large symbolism of modern life. This is rather astounding, in view of the character of the man who gave the great fund for the creation of the Palace of Peace and of his adopted nationality, which is significant of the new and progressive, rather than of the old and retardative.

The unnamed critic went on to blame the Dutch (“a downright people as ever they were”) for the failures of the building, which he described as “closely allied in general aspect to the type of some certain much-visited Flemish town halls,” although lacking their “strength and the intensity of idea which some of these latter reveals.”

But could the building, as the Times critic suggested, have served as a “representative specimen of modern architecture”? To be sure, most of the great monuments of the modernist era lay in the future; Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier, the German and Swiss-French masters of the International Style, did their most important work after World War I. Still, by the time the Peace Palace competition was announced in 1906, architecture’s future had begun to emerge in singular buildings on both sides of the Atlantic.

Indeed, of the 100 most influential buildings of the 20th century (as determined through an exhaustive survey of the world’s leading architects for the book 100 Buildings (Rizzoli 2017), eight predated the Peace Palace. Three were in the U.S.: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Robie House (Chicago; 1908–11), with its astonishing cantilevers, and his Larkin Administration Building (Buffalo; 1903–6), a kind of cathedral for workers; and the Arts and Crafts style Gamble House by the brothers Greene and Greene (Pasadena; 1907–19). In Scotland, Charles Rennie Mackintosh was developing his own arts and crafts vocabulary with his Glasgow School of Art (Glasgow; 1896–1909). And on the Continent, Otto Wagner was exploring novel facade treatments with his Post Office Savings Bank (Vienna; 1903–12), covered in flat squares of marble. Less than a mile away, Adolf Loos, with his Michaelerplatz House, nicknamed Looshaus (Vienna; 1909–11), had explored ways to make plain materials like stucco beautiful. Peter Behrens looked at the aesthetics of industrialization with his AEG Factory in Berlin (1907–9).

Perhaps most interestingly, in Holland Hendrik Berlage, the architect who in fact sued to overturn the competition results, had completed his stock exchange, the Beurs van Berlage (Amsterdam; 1896–1903), which helped make unadorned surfaces acceptable on significant public buildings. Each of these architects, though not ready to dispense with ornament entirely, pioneered new systems of decoration derived less from the classical orders than from scientific advances, non-representational art, and other contemporary sources.

Were the judges of the Peace Palace architectural competition aware of these new directions in architecture? One of the finalists was Otto Wagner, though it’s true Wagner proposed a design far less modern than the work he was doing in Vienna. Wagner must have understood that the judges — given the location and purpose of the building, and their own backgrounds — weren’t looking for a radical architectural solution. What they wanted was a building that would align the arbitration court, a new untested institution, with powerful institutions of the past, and that’s what Louis-Marie Cordonnier delivered.

In the end, however, the board set out to make the Cordonnier proposal work. So in July 1906, shortly after announcing the winning entry, board members traveled to Dunkirk, France, to see that architect’s town hall. That building so closely resembled Cordonnier’s Peace Palace design that, in Eyffinger’s words, the board members might have felt “downright cheated by the plagiarism.”

Moreover, Cordonnier, busy at his office in Lille, had little interest in relocating to The Hague, or even in making regular visits. The board persuaded him to collaborate with a Dutch architect so as to move the project forward, and eventually Cordonnier brought in the Haarlem firm of Johan van der Steur.

Even with the simplified design, the board had to ask Carnegie for additional funds — which led to his belated discovery that a brick-and-mortar library was to be a major part of the building. (When he initially offered to provide the funds for a library at the Peace Palace, Carnegie explained, he had meant a collection of books, not a library structure.)

Van der Steur’s first task was to cut costs by modifying the original design. As Eyffinger recently noted, “The building was, both on financial and aesthetic grounds, stripped of its all-too-elaborate decorations (Cordonnier was an artist first, an architect second), and two bell towers were cut out altogether. The dimensions were reduced, the ground plan altered, and the overall appearance adapted to the more modest Dutch taste — van der Steur was a very sober architect, the opposite of Cordonnier, but not exactly a creative genius.” The building, now a 234-foot square surrounding a courtyard of 102 by 132 feet, was not universally beloved in its time. Reviewing the finished building in 1913, the New York Times called van der Steur’s interventions “detrimental to a general scheme which already was by far too conventional.”

Even with the simplified design, the board had to ask Carnegie for additional funds — which led to his belated discovery that a brick-and-mortar library was to be a major part of the building. (When he initially offered to provide the funds for a library at the Peace Palace, Carnegie explained, he had meant a collection of books, not a library structure.) “I am positively wounded…. To speak of ‘The Library and Court of Arbitration’ is as if a bereaved husband were to ask plans for a sacred shrine to ‘my nephew and my dear wife,’” Carnegie wrote in a letter to David Jayne Hill, the U.S. minister in The Hague. However, through an exchange of letters and some personal diplomacy, matters were eventually smoothed over.

Meanwhile, work proceeded in the van der Steur offices. The Peace Palace’s cornerstone was laid on July 30, 1907, during the Second International Peace Conference, which was held, like the first conference (1899), in The Hague. This symbolic act preceded the actual groundbreaking by months, and splendid gifts soon began pouring in from around the world. The Russian czar sent an ornate and very grand vase — so heavy that the floor below it needed reinforcement. America’s offering was perhaps less impressive, although today the marble figure of Peace Through Justice is given pride of place at the top of the great staircase in the main entry hall, greeting visitors to the Palace in her own way. As Eyffinger, the Dutch historian, explains wryly:

America’s official gift was the marble statue representing Peace Through Justice, as it was named. After WWI, with President Wilson furious at the profitable neutrality of the Dutch during the war, the U.S. Congress did not vote in favor of a gift to the Peace Palace, and the statue (by Andrew O’Connor, and not produced until 1924) will initially have been meant for different purposes altogether. The marble lady of peace wears a wedding ring and has hands like shovels. Perhaps the records of O’Connor’s life will tell you more of the provenance of the statue!

The result is an edifice rich in allegorical detail and metaphorical allusion. Here’s de Boer, the guidebook author, describing just a bit of the decor of the Great Hall of Justice, the nobly proportioned and beautifully appointed room in which the International Court of Justice sits in session:

Remarkable for this room are its four stained-glass windows, which are a present of Great Britain. They were painted by Douglas Strachan and represent the development of mankind from its primitive days to the period when war as a means of international politics will have been banished. The painting by Albert Besnard is a gift from France. It represents a young woman separating two horsemen to prevent their fighting, while the men standing on the rocks are trying to settle their dispute by arbitration.

A grand opening was scheduled for August 1913, a month during which peace conferences were held throughout The Hague. As Eyffinger writes in The Peace Palace, “All in all, it looked very much as if the whole universe of pacifism had gravitated to The Hague — indeed, the atmosphere … was that of a joyful world reunion.” The high point came on August 28, as hundreds of dignitaries turned out for the inauguration of the Peace Palace. Old world met new, with Andrew Carnegie bowing deeply to the Dutch queen. However, as Eyffinger observes, to the Dutch public that day, it was Andrew Carnegie who was visiting royalty, likening his ride to the Peace Palace to a Fifth Avenue ticker-tape parade. Carnegie was profoundly moved by the occasion. His diary for that day reads:

Looking back a hundred years, or less perchance, from today, the future historian is to pronounce the opening of a World Court for the Settlement of International Disputes by Arbitration the greatest one step forward ever taken by man, in his long and checkered march upward from barbarism. Nothing he has yet accomplished equals the substitution for war, of judicial decisions founded upon International Law, which is slowly, yet surely, to become the corner stone, so long rejected by the builders, of the grand edifice of Civilization.

Taking his turn at the lectern that day, Carnegie predicted that the end of war was “as certain to come, and come soon, as day follows night.”

Tragically, Carnegie’s certainty did not become a reality. Exactly 11 months to the day after the opening of the Peace Palace, World War I — “the war to end all wars” — erupted when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. All seemed hopeless.

And yet …

The Peace Palace endures, and the seemingly never-ending work of the world’s peacebuilders continues.

In late September 2018, at the Peace Palace, Carnegie PeaceBuilding Conversations connected leading stakeholders from various backgrounds and generations, including underrepresented players and those directly affected by conflict and war. Presented by Carnegie institutions worldwide and their partners, the three-day program was designed to generate unexpected insights and routes for progress in promoting world peace.

At the closing event, held in the Great Hall of Justice, the winners of two notable peace prizes were announced and their extraordinary achievements celebrated. Youth-led organization BogotArt received the first Youth Carnegie Peace Prize for its “Letters of Reconciliation” project, which creates a dialogue between disconnected groups in Colombia, addressing the challenges of promoting youth participation in peace transition processes. For Leonardo Párraga, BogotArt executive director, the prize is “a direct demonstration of the power that the youth have to transform conflict and build sustainable peace.”

War correspondent Rudi Vranckx, winner of the 2018 Carnegie Wateler Peace Prize, has for more than three decades put his life on the line to give voice to people caught in some of the most dangerous conflict areas in the world. “Every word has consequences,” Vranckx reminded the audience. “Every silence does too. Silence is not an option.”

Again, old world met new. Next-generation peacebuilders are ready. Dr. Bernard R. Bot, chairman of the Carnegie Foundation–Peace Palace, forcefully invoked Andrew Carnegie, who made both the Peace Palace and the Carnegie Foundation tangible realities. “In all his ideas, he was dominated by an intense belief in the future, in progress, in education, and in a future without war. His spirit as well as his faith in the ability of individuals to better themselves, and thus the society in which they live, is a beacon of light for future generations to follow.”

Fred A. Bernstein studied architecture (at Princeton University) and law (at NYU) and writes about both subjects. He has contributed more than 400 articles, many on architecture, to the New York Times, and is a regular contributor to such magazines as Architectural Record and Architectural Digest. He has also published in journals like the New York University Review of Law and Social Change. In 2008 Bernstein won the Oculus Award, bestowed annually by the New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects for excellence in architecture writing.