A “Fool for Peace”

How can we use Andrew Carnegie’s legacy today to strengthen the case for democracy and peace, as well as the values and institutions that uphold those ideals?

By David Nasaw

The Carnegie PeaceBuilding Conversations, a three-day program presented by Carnegie institutions worldwide and their partners, was held at the Peace Palace in The Hague in September 2018. Among the event’s roster of speakers, David Nasaw, the biographer of Andrew Carnegie and Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. Distinguished Professor of History at the CUNY Graduate Center, examined the great Scot’s legacy both historically and in terms of more recent developments. Here follow Professor Nasaw’s prepared remarks.

September 24, 2018 | The Hague, Netherlands

We are here today because of a funny-looking little Scotsman, who, in his high-heeled boots stood no more than five feet tall, a strange-looking gnome of a man who resembled Santa Claus in a top hat or a miniaturized Karl Marx.

We are here today because that little man believed in evolution, in reason, in humanity.

We are here today because that little man had a big voice and the money to make himself heard and be taken account of.

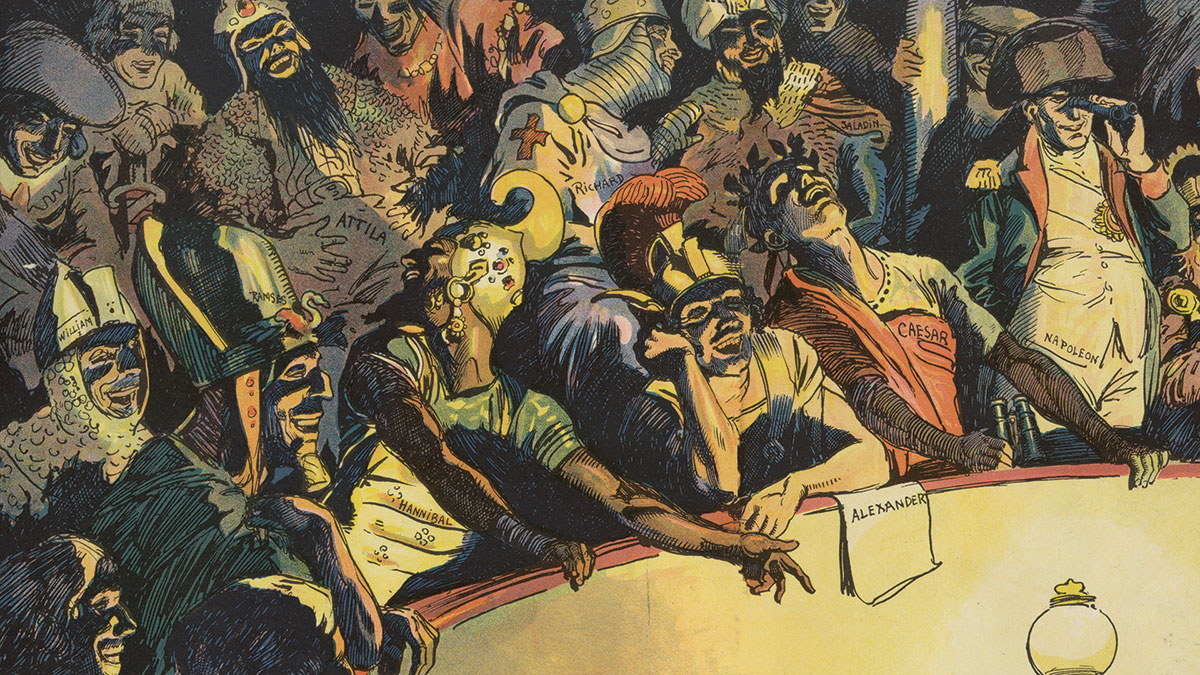

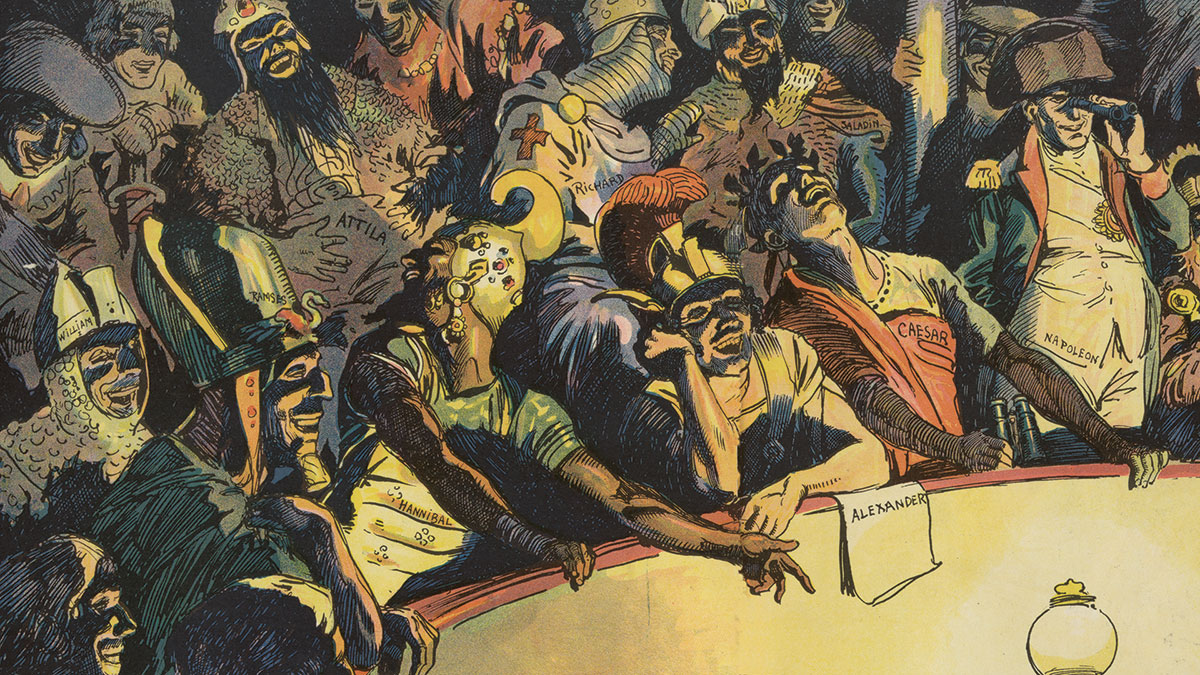

We are here today because in an age too much like our own — an age of armaments escalations, build-ups, and races, an age where military men were saluted for their bravery and stout hearts and peace activists ignored or ridiculed as utopians, cranks, dreamers — that little man dedicated himself and a good part of his fortune, his welfare, his health, and his reputation to campaigning for peace.

We are here today to celebrate, learn from, and carry on the legacy of a child of the Scottish Enlightenment; a man of the 19th century, the century of light and progress; an enthusiast, a utopian, a fool, a crank, a dreamer, but also a pragmatist and politician who preached the gospel of peace on earth.

Andrew Carnegie had learned from Herbert Spencer that the laws of evolutionary progress guide change over time, that history has both purpose and direction, that the world was getting more prosperous, more civilized, more humane. The age of barbarism had been marked by savagery, the inability of men to settle disputes other than through violence, the organized killing of innocent men by innocent men. The age of civilization would, on the contrary, be marked by the replacement of violence with reason in the settling of domestic, personal, and international disputes.

“You will find the world much better than your forefathers did,” Carnegie declared in his second rectorial address to the students of St. Andrews, delivered just five years into the new century. “There is profound satisfaction in this, that all grows better; but there is still one evil in our day, so far exceeding any other in extent and effect, that I venture to bring it to your notice.… There still remains the foulest blot that has ever disgraced the earth, the killing of civilized men by men like wild beasts as a permissible mode of settling international disputes.”

![]()

Carnegie was not alone in campaigning for peace. The first half of the 19th century, in the U.S. and Britain and on the continent, witnessed the proliferation of local, regional, and national peace and arbitration societies, congresses, and campaigns. A major international peace conference in 1849, to which the American peace societies sent as a delegate a former slave, condemned war and called for compulsory arbitration, reduced spending on armaments, the creation of an international “High Tribunal,” and a Congress of Nations.

The early 19th-century peace movement did not end well — it was a victim of the Crimean War, of disagreements about what constituted good and bad conflicts, just and unjust wars, and of unresolved and perhaps unresolvable questions about whether the citizens of enslaved nations in Europe, like the Italians, had the right to fight for their freedom. This organized peace movement did not die — it instead entered on a new phase, one led by international lawyers and statesmen who argued that after centuries of warfare, peace would have to be built, step by step, through the creation of a body of international law and arbitration treaties that called for the peaceful resolution of disputes.

Peace, disarmament, and arbitration activists like Andrew Carnegie had, by the last quarter of the 19th century, come to believe that their cause was not only just, but achievable. They pointed, with pride and hope, to 1872 and the peaceably arbitrated resolution of the “Alabama Case,” which had pitted Great Britain against the United States over the American demand for compensation for the damage caused by British-built confederate warships, and to 1895, when the Americans and the British peaceably settled another dispute over the boundary between Venezuela and British Guiana. “Truly,” Carnegie wrote Prime Minister Gladstone, arbitration as a substitute for war “seems to me the noblest question of our time.” The Americans and the British would set the example which the rest of the world would soon follow.

The scaffolding for a new, civilized world order was already in place — here, at The Hague, where a Permanent Court of Arbitration had been established at the international conference in 1899, called by Czar Nicholas II, and attended by the representatives of 27 nations. The promise of peace through arbitration at The Hague was affirmed when, in December 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt persuaded Britain, Germany, Italy, and Venezuela to submit their dispute over Venezuela’s refusal to pay its debts for arbitration by the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

“The world took a long step upward yesterday,” Carnegie wrote the president the day after the four states had agreed to arbitration, “and Theodore Roosevelt bounded into the short list of those who will forever be hailed as supreme benefactors of man.” In a “New Year Greeting” published in the New York Tribune, Carnegie declared that Roosevelt, in “breathing life into The Hague tribunal, the permanent high court of humanity, for the peaceful settlement of international disputes,” had moved humanity a step closer toward the “coming banishment of the earth’s most revolting spectacle — human war — the killing of man by man.… The complete banishment of war draws near. Its death wound dates from the day that President Roosevelt led … opposing powers … to the Court of Peace, and thus proclaimed it the appointed substitute for that which had hitherto stained the earth — the killing of men by each other.”

To celebrate the dawn of this new era, Carnegie, in April 1903, committed $1.5 million (about $43 million today) for the erection of a Peace Palace to house the Permanent Court of Arbitration and a library. Mankind was now set on the path to peace — and progress along it appeared inexorable.

In October 1904, U.S. Secretary of State Hay issued a call for a second peace conference at The Hague.

In June 1905 Japan and Russia ceased hostilities and agreed to negotiate peace terms, with President Roosevelt as arbitrator, in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Carnegie, buoyed by events, stepped up his personal and now full-time campaign for peace. In October 1905, in his second rectorial address at St. Andrews, he delivered an overly long treatise — how anyone sat through it is beyond me — on the history of peace activism, on the folly, the madness, the immorality, the inhumanity of war, and the need to eliminate it from the face of the earth through “Peaceful Arbitration.” He urged his hearers, university students, to resist the clarion call to arms. There was no glory to be had by putting on a uniform and killing one’s fellow men. “We sometimes hear, in defense of war, that it develops the manly virtue of courage. This means only physical courage, which some animals and the lower order of savage men possess in the highest degree. According to this idea, the more man resembles the bulldog the higher he is developed as man.” It was to educate the public to the true meaning of courage, of heroism, that Carnegie had the year before created his Hero Funds. He was prouder of his Hero Fund than of any of his other endowments. “It grew out of his intense conviction,” his friend and one of the original commissioners Frederick Lynch insisted, “that it took just as much heroism to save life as it did to take it, whereas the man who took it got most of the recognition.”

“Most of the monuments in the world,” Carnegie had discovered, to his dismay, were “to somebody who has killed a lot of his fellowmen.” That was not heroism. His Hero Fund would call attention to, recognize, and reward the true heroes of the world.

With every utterance, Carnegie made new enemies and enflamed old ones. Teddy Roosevelt, whom Carnegie regarded as his partner in peace, was near apoplectic at the Scotsman’s dismissal of the manly military virtues, at Carnegie’s delight that fewer and fewer young men appeared to be volunteering for military service, and his call on university men to resist putting on uniforms and defending their nations. In November 1905 he wrote Whitelaw Reid that he had tried hard to like Carnegie

but it is pretty difficult. There is no type of man for whom I feel a more contemptuous abhorrence than for the one who makes a God of mere moneymaking and at the same time is always yelling out that kind of utterly stupid condemnation of war which in almost every case springs from a combination of defective physical courage, of unmanly shrinking from pain and effort, and of hopelessly twisted ideals.… It is as noxious folly to denounce war per se as it is to denounce business per se. Unrighteous war is a hideous evil; but I am not at all sure that it is worse evil than business unrighteousness.

![]()

Carnegie was undeterred by the criticisms, by the caricatures, by the insults to his manhood. What worried him was that, while mankind appeared to be progressing toward peace, there were fearful signs of war on the horizon. The British and the Germans were engaged in an escalating battle to build bigger and bigger dreadnoughts, with other nations now entering the fray. Though Carnegie Steel was making a fortune outfitting new battleships with steel armor, Carnegie insisted that armor was for defensive, not offensive, purposes. And, to his partners’ dismay, he campaigned for an end to this arms race.

Carnegie hoped and expected that the subject of disarmament would be discussed at the Second International Peace Conference in The Hague, which, after postponements, was scheduled to meet in June 1907, or at a disarmament conference in London, which he actively proposed and promoted. In the meantime, in preparation for the Hague conference, he took an active, oversized role in funding, organizing, and convening a massive and massively publicized meeting of the National Arbitration and Peace Congress at Carnegie Hall in April 1907.

The meeting was a triumph — but it was only a meeting, an exhortation, and a prayer. The real work of peace was to be accomplished at The Hague that summer. Carnegie was not content to leave the business of peacemaking to the delegates. In early June 1907 he attended Kaiser Wilhelm II’s annual regatta at Kiel in northern Germany, hoping that he would be able to arrange a personal meeting and a personal connection to the kaiser. He did not get much of a chance to do so — the kaiser was more interested in his yachts than in talking peace to the strange little loquacious Scotsman about arbitration and The Hague.

From Kiel, Carnegie and his wife, Louise, boarded a special railroad car provided him by the kaiser, which, with the Dutch government’s cooperation, arranged for his through passage to The Hague. He arrived — as a private citizen — while the conference was in process and spent the next few days as cheerleader and publicist. The second Hague conference would continue to meet through the fall, long after Carnegie had departed. The fact that little was accomplished on naval disarmament, compulsory arbitration, a League of Peace, or the organization of an international police force neither deterred nor discouraged Carnegie. More nations had participated in 1907 than in 1899 and the conference had adjourned with a resolution to meet again, though no date was set for a third conference. (A date was eventually set: 1915, but by then it was far too late for peace. There would be no third peace conference at The Hague.)

Despite the failures of the second Hague conference, Carnegie remained confident that naval disarmament, compulsory arbitration, and a League of Peace would come to pass, but perhaps not just yet. The nations of the world had failed to bring about the desired end at their conference at The Hague, but Carnegie would succeed where they had failed, through the power of personal diplomacy. He had already established firm connections with the leaders of the U.S. and the U.K., helped along by healthy contributions to the Republicans in America and the Liberal Party in the U.K. He had lesser but still friendly personal relationships with the leaders of France and Italy. He had failed, however, and failed rather spectacularly, to make any headway with Kaiser Wilhelm II. But he did not despair. He would enlist as his surrogate peacemaker a man who would have no trouble gaining an audience with and sitting down with the kaiser. Theodore Roosevelt would be his representative, his agent, his envoy, his liaison to the European heads of state. While president, Roosevelt had been prohibited by custom from leaving the country. His term of office would, however, end in March 1909 and he would be free to travel the world on Carnegie’s behalf.

“Although we no longer eat our fellow-men nor torture prisoners, nor sack cities killing their inhabitants, we still kill each other in war like barbarians. Only wild beasts are excusable for doing that in this, the twentieth century of the Christian era, for the crime of war is inherent, since it decides not in favor of the right, but always of the strong. The nation is criminal which refuses arbitration.”

— Andrew Carnegie, letter to the trustees of the Carnegie Peace Fund (which would become the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace), December 14, 1910

Roosevelt’s first priority, however, was not making peace, but shooting as many large animals as he could in Africa. Carnegie made a deal with the ex-president. He would provide the funds Roosevelt needed for his African expedition. When the killing was finished — after the slaughter of over 500 African animals, 55 species of large mammals, and 11 elephants — Roosevelt would leave Africa for Europe to do Carnegie’s bidding. “After Africa, then the real ‘big game,’” he wrote Roosevelt. “Meet the men who rule European nations, then you have a source of power otherwise unobtainable — You promise to become the ‘Man of destiny.’”

Carnegie barely took a breath now — he was more frightened than ever by the escalating naval arms race and tensions in Europe. Bigger and bigger armies and navies did not ensure peace, but rather provoked war. Men with pistols in their hands were more likely to shoot one another; nations with armies and navies more likely to engage in war, he proclaimed at the annual meeting of the New York Peace Society at the Hotel Astor in April 1909. It did not require much imagination to envisage a scenario where a minor incident might lead to world war, perhaps a drunken altercation between British and German marines. “Under the influence of liquor … one is wounded, blood is shed, and the pent up passions of the people of both countries sweep all to the winds.”

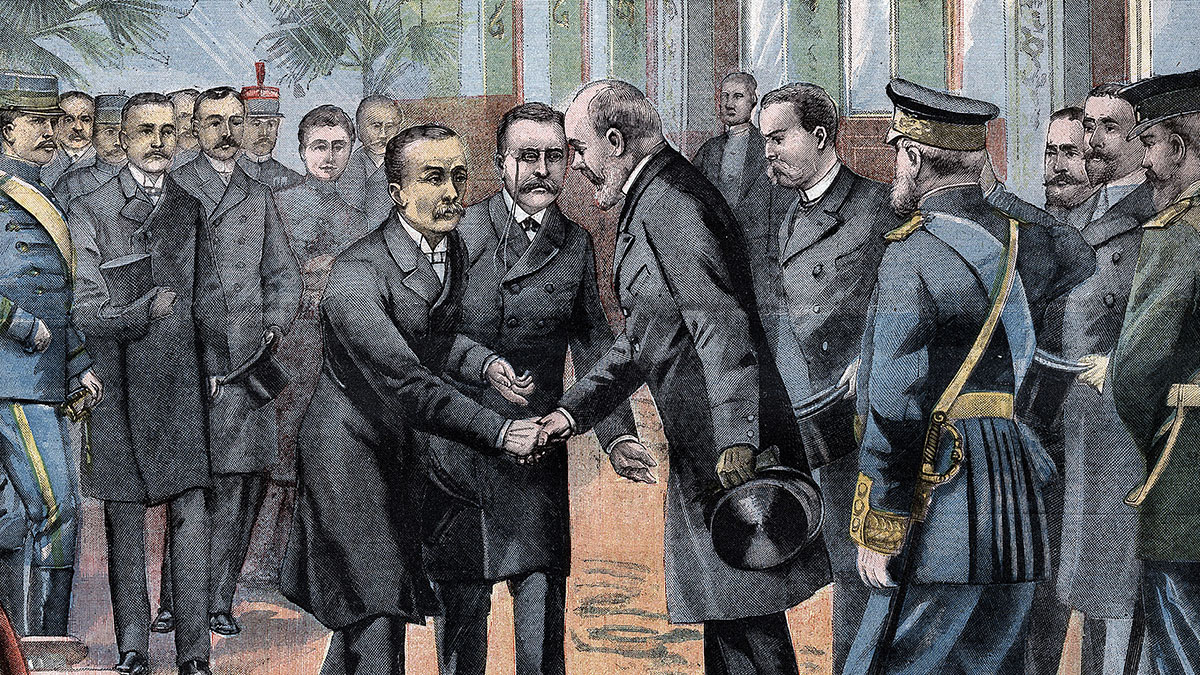

In April 1910 Roosevelt arrived in Europe from his African adventures and was greeted like a conquering hero in Paris, then in Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Norway (where he received the Nobel Prize for his role in arbitrating an end to the Russo-Japanese War). Carnegie’s plan was that Roosevelt meet first with Kaiser Wilhelm II in Berlin and enlist his support for a compulsory arbitration treaty, and then go to London to meet with the leaders of the British government to secure their approval. This grandest of schemes was derailed, temporarily, when on the eve of Roosevelt’s arrival in Berlin, Edward VII of Britain died, and all future diplomatic activity ground to a halt. But even had the king (who happened to be the kaiser’s uncle) lived, Carnegie’s grand scheme was destined for failure. Roosevelt had no intention of doing his bidding.

“Carnegie … had been asking me to try to get the Emperor committed to universal arbitration and disarmament,” Roosevelt wrote his friend George Trevelyan in Britain. “Carnegie’s purposes as regards international peace are good, although his methods are often a little absurd.” Roosevelt refused to present the kaiser with Carnegie’s “absurd” peace proposals. He indirectly raised the possibility of Germany’s slowing the naval arms race with Britain, but indicated he would not be disturbed if there were no movement towards disarmament. Roosevelt assured the kaiser that he was “a practical man and in no sense a peace-at-any-price man.”

Roosevelt not only failed to secure the agreement of the kaiser to move forward but, in the wake of King Edward VII’s death and the hubbub over succession and the coronation of a new monarch, he gleefully postponed and then canceled his meetings with the leaders of the ruling Liberal Party in Britain.

Carnegie’s plans had fallen flat — there would be no arbitration treaty, no disarmament conference in London, no League of Peace in The Hague. But he did not give up hope. Instead he shifted his focus from Europe to Washington, where he intended, under the leadership of President Taft, to secure passage of a meaningful, near compulsory bilateral treaty of arbitration between the U.S. and Britain, after which similar treaties would be negotiated with France, Germany, Russia, Italy, and Japan, culminating in the creation of a functioning League of Peace.

To help Taft get his proposal through the Senate, Carnegie organized — and donated $10 million dollars to establish — his “peace trust,” the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP). He named Elihu Root, former secretary of war and state and now senator from New York, as its first president. His letter to his trustees made clear his intentions: “Although we no longer eat our fellowmen nor torture prisoners, nor sack cities killing their inhabitants, we still kill each other in war like barbarians. Only wild beasts are excusable for doing that in this, the twentieth century of the Christian era, for the crime of war is inherent, since it decides not in favor of the right, but always of the strong. The nation is criminal which refuses arbitration.”

Taft’s treaties ran into trouble almost immediately, when it became clear that the Senate Foreign Relations Committee was not going to sign a treaty which obligated the nation to arbitrate issues of “honor” or “national interest” without the Senate’s explicit approval. Teddy Roosevelt, now on the warpath against his successor, declared, in no uncertain terms, that the nation that pledged to arbitrate its differences would end up dishonored and impotent, like the man who, when his wife was assaulted by a ruffian, took the ruffian to court instead of attacking him on the spot. Carnegie wanted to fight back against Roosevelt and treaty opponents by launching a publicity campaign organized and funded by his new Endowment, but Elihu Root refused to do so. Carnegie did not argue — as a matter of principle, he did not overrule the men he had chosen to run his various philanthropic endeavors. Instead he took $10,000 of his own money to pay for clergymen to travel to Washington and lobby their senators. Again, his efforts came up short and Taft’s arbitration treaty bill was eviscerated by amendments.

Carnegie blamed Taft’s lack of political skills for the defeat, refusing to recognize the frightening insularity of America’s leaders. He had never paid much attention to public opinion, believing that he had the money and the skill to educate the public to his thinking. It was a fateful, terrible mistake to build peace from the top down, as Carnegie had attempted to do, without simultaneously working from the bottom up. Carnegie’s trust in the American public and in politicians — his optimism that they too were reasonable men and women — was falsely placed. There was work to be done — then and now — in the United States. He did not do it, but we must. As I wrote the final draft of this talk, the front page of the New York Times carried an article, bylined The Hague: “On War Crimes Court, U.S. Sides with Despots, Not Allies.”

The Hague conference had failed, Roosevelt’s mission for peace had ended in failure, and the treaties of arbitration which Taft had attempted to push through Congress had been destroyed by Congress. The arms race in Europe continued apace.

And still, the “Star-Spangled Scotsman,” as he proudly called himself, refused to give up. In February 1914, bowing to Elihu Root’s wish to keep the Endowment out of political controversies, Carnegie endowed a second agency, the Church Peace Union (known today as the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs) with $2 million, with the understanding that it would take a more activist role than the Endowment could. With the leaders of the new organization, an ecumenical group of churchmen, all peace activists, he planned an international conference to be held in Germany in August.

And then, the unthinkable. Carnegie, as had been his routine for decades, spent the summer of 1914 in Scotland, when, as he had predicted, the spark he had spent the last 20 years trying to extinguish took flame, and absent any compulsory arbitration mechanisms or institutions, the nations of Europe resorted to violence to settle a local dispute between Austria and Serbia. His first task was to rescue the Church Peace Union delegates from Britain and the United States who had been trapped in Germany when war was declared. That accomplished, he returned to the United States and went immediately to Washington, where he implored President Wilson and the American government to do what it could to broker some sort of peace agreement. He failed, the war ground on, the killing accelerated.

Carnegie celebrated his 79th birthday in November 1914. In December he predicted that if a League of Peace were not established at the end of the war now raging, the vanquished would rise up again to renew the cycle of bloodshed.

In March 1915 he was asked in an interview with the New York Times if he had “lost faith in the peace impulse which centers at The Hague.”

“Certainly not. I verily believe that in this war exists the most impressive, perhaps the only argument which could induce humanity to abate forever the curse of military preparation and the inevitably resultant woe of conflict.… This war staggers the imagination.… I do not underestimate its horror, but I hope, and I believe that this very horrible, newly barbaric excess will so revolt human nature against all things of the kind that the reaction will be great enough to carry us into the realms of reason. And the realms of reason are the realms of peace.”

This was to be his last interview.

He retreated into silence, stopped writing, seeing visitors, speaking, corresponding; he refused to read the newspapers. His friends were distraught, as, of course, was Louise, his wife, who did not recognize the once voluble, active little man who could not stop talking. They were convinced he had suffered some sort of a nervous breakdown, brought about by his failure to do anything to stop the Great War. The supreme optimist had in the end been defeated by the reality of man’s inhumanity to man. And had ceased to communicate with the world around him.

On November 10, 1918, the day before the armistice was signed ending World War I, he took up pen again to write a last letter to Woodrow Wilson. “Now that the world war seems practically at an end I cannot refrain from sending you my heartfelt congratulations upon the great share you have had in bringing about its successful conclusion. The Palace of Peace at the Hague would, I think, be the fitting place for dispassionate discussion regarding the destiny of the conquered nations, and I hope your influence may be exerted in that direction.”

Wilson’s response was generous. “I know your heart must rejoice at the dawn of peace after these terrible years of struggle, for I know how long and earnestly you have worked for and desired such conditions as I pray God it may now be possible for us to establish.” While Wilson did not know where the peace talks would be held (they would end up at Versailles, not The Hague), he was sure that Carnegie would “be present in spirit.”

And Woodrow Wilson may have been right.

We are here today because Andrew Carnegie remains with us in spirit. He was a man of the 19th century who hoped for better in the 20th century. We are now nearly two decades into the 21st. Might we not take something away from Andrew Carnegie’s crusade for peace, failed though it was. Let us pause — at this moment, in this grand Palace of Peace, and look back across the desolate dark century that has passed, the world wars, the genocides, the killing fields. Without forgetting the horrors of our recent past and the dismal failures to build a lasting peace, let us remember, celebrate, and build upon this little man’s dreams. Let us renew, with him, our commitment to work towards a future when reason and humankind take the final step forward on the path from barbarism to civilization.