A century after his death, Andrew Carnegie remains an integral part of Pittsburgh. This town is where he got his first job, built his professional career, and carried out much of his extraordinary philanthropic vision. In the Steel City, Carnegie is a household name. It is a place where locals pronounce “Carnegie” as the Scots do.

Andrew Carnegie’s family settled in a working-class Pittsburgh suburb after journeying from Scotland to New York City, then taking a three-week trip by steamboat to Pennsylvania. It was here that Carnegie started work as a bobbin boy in a cotton mill at age 13 before building a career in railroads, steel, and bridges to eventually become one of his era’s most successful businessmen.

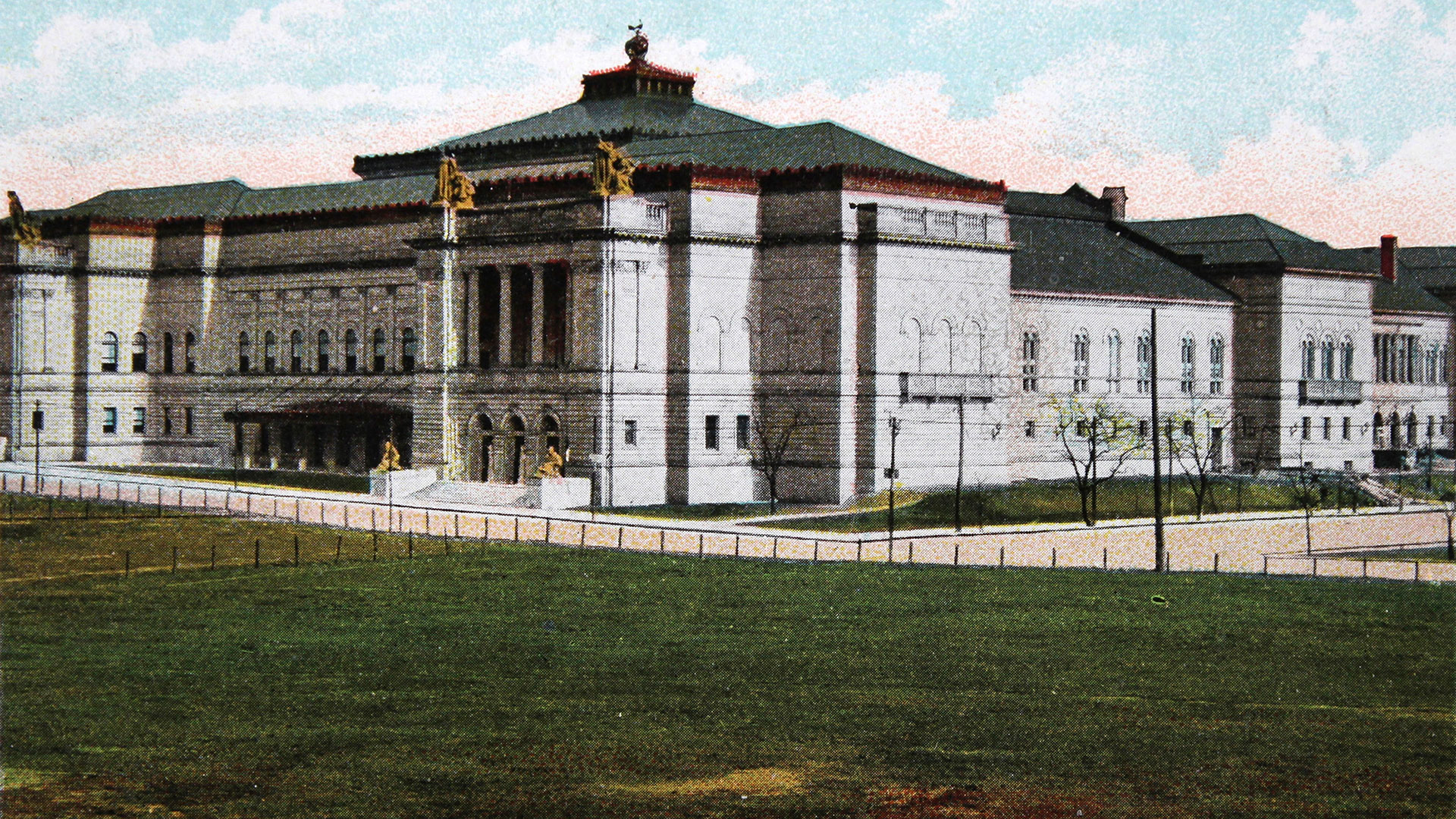

Carnegie used his wealth and ideas to establish more than 20 institutions in North America and Europe, translating his passion for art, culture, and education into reality for so many others. Pittsburgh now calls itself home to more Carnegie institutions than any other city.

Carnegie’s wealth was important, but his ideas — his philosophy of giving — were even more critical, so powerful that more than a century later they continue to attract leading professionals and volunteers alike. Are the ideas on which he built his organizations and the goals he set for them still relevant today?

Look just at Pittsburgh. Today, the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission is preparing to celebrate its 10,000th hero. Carnegie Mellon tops university rankings in critical areas such as computer science and artificial intelligence. Carnegie Museum of Art was the first in the United States to place a strong focus on contemporary art. Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh welcomes nearly three million visitors each year, and the Carnegie Museum of Natural History contains one of the world’s greatest archives of biodiversity and the history of life.

In the lead-up to the centennial year of his passing in 1919, Carnegie institutions around the world are hosting a series of events titled Forging the Future, honoring Andrew Carnegie’s commitment “to do real and permanent good in this world,” while also working to keep his legacy alive and vital into the next century.

The next Forging the Future event, “The Power of One: A Tribute to the Power of the Individual,” will take place on June 12 and be hosted by four Pittsburgh institutions: the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, and Carnegie Mellon University. Celebrating the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission’s 10,000th hero, the event will recognize civilians who have risked — and sometimes actually lost — their lives trying to save the lives of others. Even before he signed the deed establishing the commission in 1905, Carnegie had long felt strongly about acknowledging the heroism of individuals.

“He said we live in a heroic age and indeed, we still do,” says Carnegie Hero Fund Commission president Eric P. Zahren. “We’re still seeing people risk their lives on a consistent basis and we don’t expect that to change. Even now, in our disconnected, technology-driven world reportedly void of human compassion, as it is too often presented, heroes abound.”

Over the last 114 years, acts of heroic bravery have changed. It’s unlikely, for example, that modern heroism will involve a runaway horse buggy — but Andrew Carnegie’s commitment to honoring brave civilians endures. The Hero Fund recognizes acts of courage as varied as a cafeteria clerk who stopped her car to help a wounded police officer to a business owner who saved a woman falling from a bridge. By awarding medals and financial rewards — which may entail paying the educational costs for the hero’s children — the impact of acts of personal bravery can ripple across generations.

Like many of his philanthropic endeavors, the commission exemplifies that celebrating the power of individuals, appreciating art, and fostering scientific exploration remain as relevant today as in the 19th century.

Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, which consists of Carnegie Museum of Art, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Carnegie Science Center, and The Andy Warhol Museum, is a partner for the “Power of One” event and an institution built around the local Pittsburgh community.

“Andrew Carnegie founded the museums to bring the world to Pittsburgh,” says Bill Hunt, chair of the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh Board of Trustees. “At that time, people didn’t travel outside their home base, people did not have disposable income, and their educations were much more restricted, if they had education at all. He wanted to change that, to open up the world to the people in the city and give back to the people of Pittsburgh.”

As an immigrant, Carnegie believed education was a great equalizer and was committed to ensuring that his philanthropy would create “ladders on which the aspiring can rise.” Today, the museums bring more than 150 special exhibitions, films and theatre shows to the city each year. The history museum examines the impact of humanity on nature and the environment, while the Carnegie Science Center’s STEM program works to build enthusiasm and interest so that Pittsburgh’s children might grow up to consider careers in specialized fields.

As another step on the ladder on which the aspiring can rise, Andrew Carnegie — the “Patron Saint of Libraries” — knew libraries could offer cultural resources for newcomers to America. Growing up in Pittsburgh, he worked long hours and had no access to formal education, but a local merchant lent him books, which solidified his belief in the immense potential of libraries.

In recent years, Pittsburgh, like many American cities, has seen an increase in immigrants, like the Carnegie family, welcoming more than 22,000 new residents from 2010 to 2016. Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh offers English classes, supporting those new to the city, as well as providing materials in other languages and holding naturalization ceremonies. Over the years the library’s 19 locations have grown along with the city, and consistently served its residents’ needs.

“Our story is really interwoven into the Pittsburgh story,” says Mary Frances Cooper, Library president and director. “The library has been here for every challenge and opportunity that Pittsburgh has faced.”

When Carnegie said, “Pittsburgh entered the core of my heart when I was a boy and cannot be torn out,” he could not imagine that almost 100 years after his death he would remain a vital part of the Steel City. Andrew Carnegie would not have been the same man without Pittsburgh and, without him, Pittsburgh would not be the city it is today.