Toward the end of Andrew Carnegie’s life, achieving world peace became the philanthropist’s primary occupation. Civilized nations had abandoned practices of slavery and dueling; the telephone, trains, and steamships were globalizing communications; and the Great Powers had been at peace since the 1871 Franco-Prussian War — surely, the abolition of war would follow.

Until his death in 1919 (two months after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles), Carnegie worked tirelessly to “hasten the abolition of international war.” For Carnegie, war was “the foulest stain that remains to disgrace humanity, since slavery was abolished.”

Given that the world today is still very much mired in war and conflict, it is fitting that the family of Carnegie institutions opened the Forging the Future series with an event that draws upon the lessons of the past century as we look — it is hoped — to forge a more peaceful future.

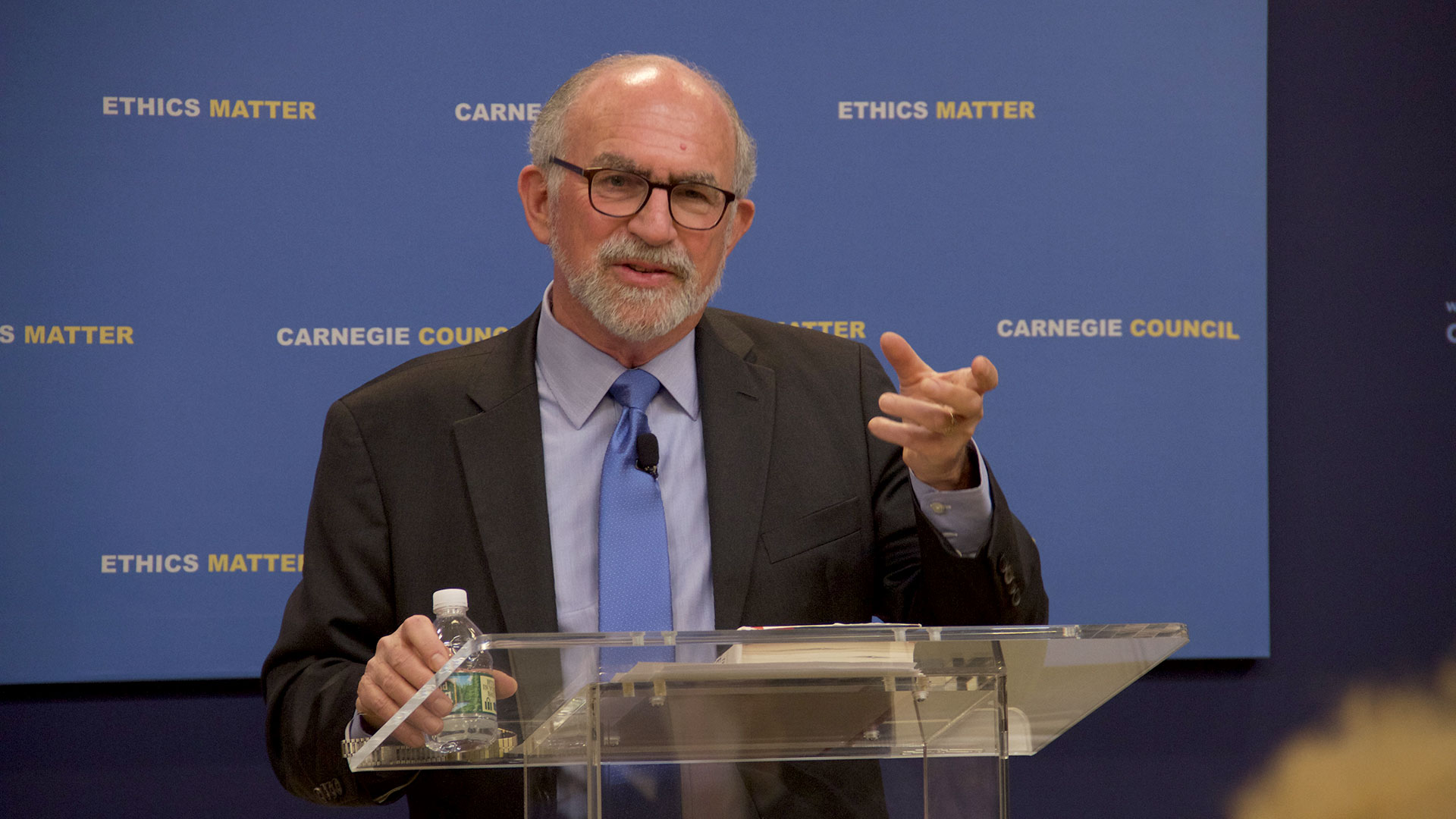

On April 26 the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs and Carnegie Corporation of New York hosted a conversation in New York City with author and Duke University professor Bruce W. Jentleson.

Beyond academia, Jentleson has also helped shape U.S. foreign policy in a range of different positions at the State Department and has worked with various presidential administrations. From coordinating communications between former PLO leader Yasser Arafat and then-Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin in the 1990s to serving on the National Security Advisor Steering Committee of the 2012 Obama presidential campaign, Jentleson has been involved in some of the most critical diplomatic and security negotiations of the past two decades.

In a discussion centering around his recently released book, The Peacemakers: Leadership Lessons from Twentieth-Century Statesmanship (W. W. Norton), Jentleson posed the fundamental question of whether leaders shape history — or vice versa. For Jentleson, individuals make the critical difference, be they political mandarins or ordinary citizens. He made a compelling case for the importance of vision, courage, and moral authority in facilitating the breakthroughs that can bring about real and lasting peace.

In what proved to be the highlight of the talk, Jentleson described a key interaction between then-U.S. national security advisor Henry Kissinger and former Chinese premier Zhou Enlai around the time of the U.S.-China rapprochement of 1972. When Kissinger entered the first — very secret — meeting (dubbed “Operation Marco Polo”), he extended a handshake to Zhou. Kissinger knew that, nearly 20 years earlier, then-secretary of state John Foster Dulles chose to shake hands with former Soviet foreign minister Molotov, but he refused to take the hand of Zhou. Jentleson credits Kissinger for understanding the significance of a handshake in this context, and thereby possibly changing the course of history.

Jentleson recounted several similar moments in 20th-century history when peace was established thanks to the — as one can see in hindsight — visionary actions of individuals.

Today, Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Peace continues to celebrate Andrew Carnegie’s commitment to greater international understanding, justice, and peace by using its convening power to bring together leaders from around the world to share ideas, reflect on experiences, and engage in public conversations. These dialogues are a vital stepping stone toward achieving “real and permanent good in this world” — and perhaps even toward Andrew Carnegie’s dream of world peace.