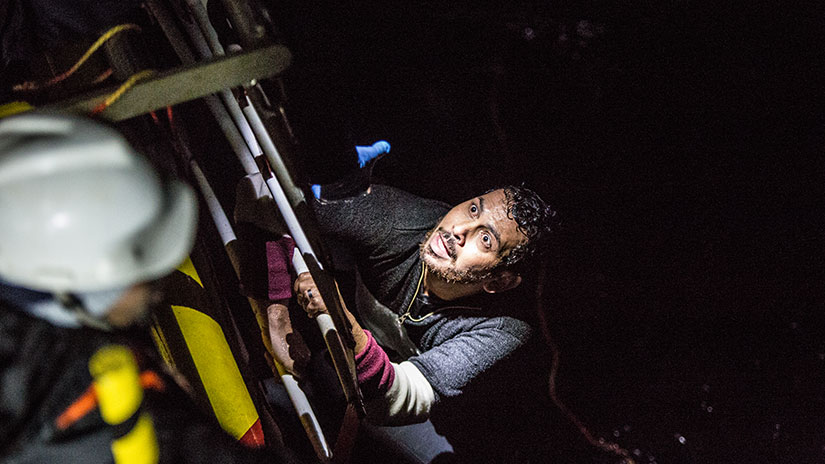

© Jason Florio/MOAS.eu 2016. All rights reserved. Visit here for more.

Christopher Catrambone’s foundation runs on a simple, but critical belief: no one deserves to die at sea. His organization, the Migrant Offshore Aid Station, or MOAS, has rescued more than 30,000 people over the last three years, many of them from Syria.

Catrambone and his wife founded MOAS shortly after an incident in October 2013, when a boat carrying about 400 children, women, and men from Africa sank off an Italian island. The Louisiana native, who has been living in Malta for the last decade, said he felt compelled to address the growing number of such tragic deaths. He estimated that so far he and his wife have given $8 million to the cause.

“I have so much satisfaction because the reward is making a difference,” said Catrambone, a philanthropist and entrepreneur who also runs a multimillion-dollar insurance company. “It’s not money that’s the reward. And the awesome feeling of helping people in their most dire moment is great satisfaction.”

MOAS has served as a model for many organizations that have since started their own search and rescue operations at sea, including Save the Children and Médecins Sans Frontières, Catrambone said. MOAS has rescued people from all walks of life, including the elderly and children. One Syrian girl arrived as an unaccompanied minor after her mother was killed on the route to the boat.

“There are a lot of terrible stories and this is what keeps us going,” Catrambone explained. “We rescue them, we talk to them, we document their stories. Because their stories are the most important message they can get out—why did they decide to get in a rickety boat and flee?”

After six years, the Syrian conflict has claimed an estimated 470,000 lives. About 13.5 million people require humanitarian assistance and over half the population has been forced from their homes. More than 5 million people have fled Syria since 2011, and millions more are displaced inside the country.

The United Nation’s funding appeal for Syria remains unmet. And in early June, UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, warned that unless urgent funding is received, some 60,000 Syrian refugee families in Jordan and Lebanon will be cut from a vital monthly cash assistance program as early as next month.

But philanthropy is making a notable difference in some areas. MOAS is an example of how it has saved lives, after thousands of refugees set out on dangerous journeys in hopes of reaching safety. As the refugee crisis spilled into the Middle East and Europe, a growing number of individuals, foundations, and businesses responded by helping refugees access everything from cell phones and electricity, to housing and educational opportunities.

In April Jordan’s Azraq refugee camp started using a solar plant—the first ever built in a refugee setting—thanks to the IKEA Foundation. The plant supplies electricity to 20,000 camp residents (construction of the plant provided income for more than 50 refugees).

Some tech companies have also stepped in. Google supports Project Reconnect, which is providing 25,000 Chromebooks to organizations serving refugees in Germany. Google also recently created the Searching for Syria website to inform people about the crisis. Microsoft Philanthropies has a number of initiatives, just last month signing an agreement with the UN to help with job creation in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, the countries that have absorbed most of Syria’s refugees.

The Conrad N. Hilton Foundation has awarded more than $5 million in grants and recently approved another $1 million for Save the Children and the International Rescue Committee (IRC). Airbnb aims to provide temporary housing to 100,000 refugees over the next five years. UPS, Uniqlo, H&M, and the United Nations Foundation have also donated, as have many individuals and organizations from the Gulf and the Middle East, said Joung-ah Ghedini-Williams, emergency response coordinator with UNHCR in Geneva. The need is still enormous, she said, but unlike other crises, such as that in Yemen, the media and the public are still paying close attention.

“With the Syrian crisis, what we’ve seen, even six years into it, is it’s one of the emergencies that is most supported,” she said. “And by that I mean not only financially, but emotionally, morally, and in terms of public support.”

Ghedini-Williams said there are many benefits to building partnerships, including innovation and increasing awareness. For example, IKEA helped create freestanding refugee housing units that have locks and solar panels, which are critical for girls and women’s safety, she said. And through its in-store campaign that donated money for every light bulb purchased, more people have become informed about issues facing refugees, she said.

“This situation just continues to get more politicized,” Ghedini-Williams said, “so it’s about how do we reach new ears and wallets and feet that are going to march to their countries’ parliaments or to their mayors’ offices and really advocate for better asylum and protection and assistance for refugees.”

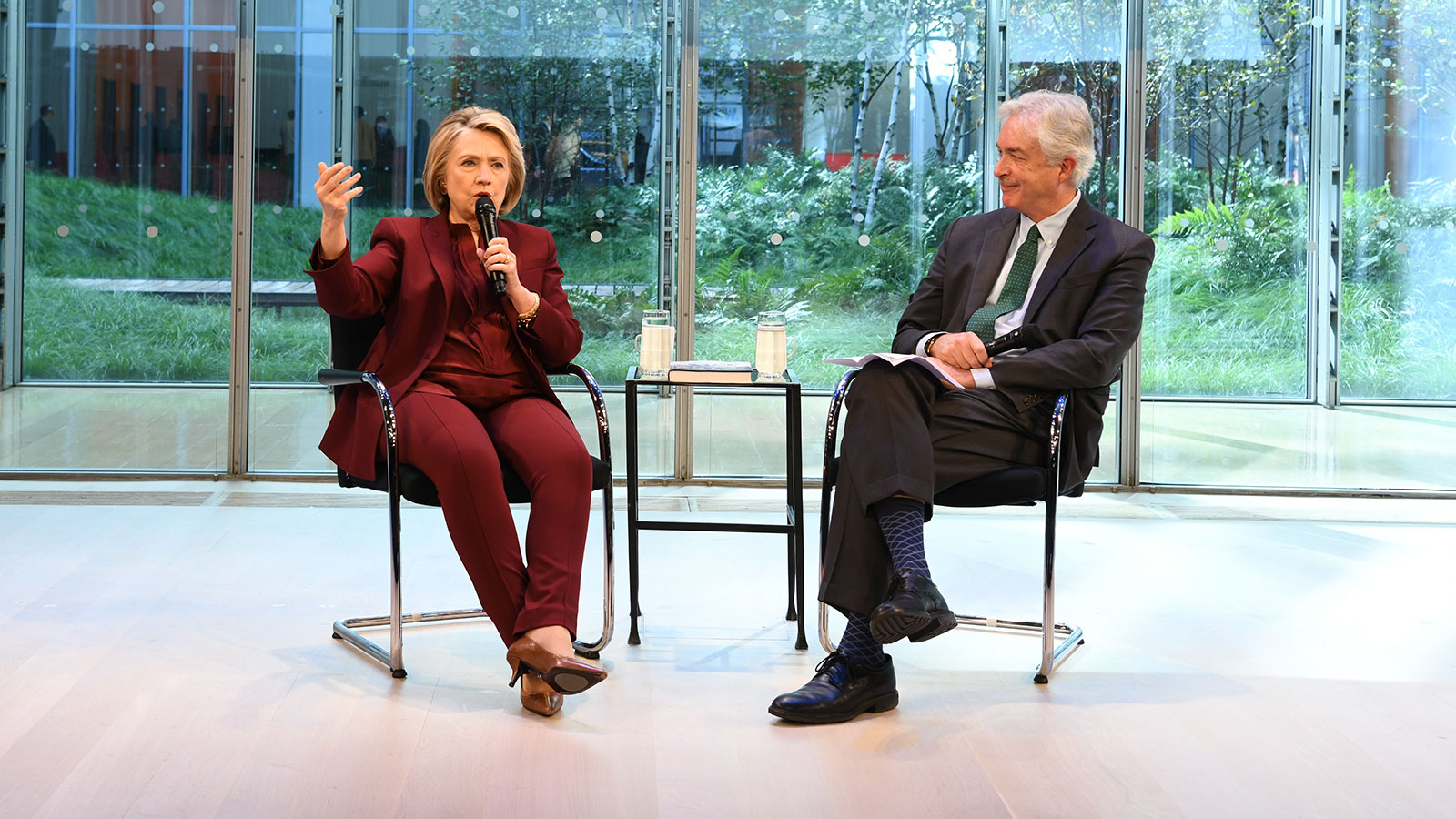

In addition to the vast humanitarian needs, the Syrian conflict also created an educational crisis, said Hillary Wiesner, program director for Transnational Movements and the Arab Region at Carnegie Corporation of New York. The foundation has supported such programs as the International Institute of Education’s Scholar Rescue Fund, which helps threatened scholars, as well as the Global Platform for Syrian Students.

The conflict also illustrates the need to ensure that cultural preservation is funded, as many museums and cultural heritage sites of great value have been damaged or destroyed. “I do think Syria has changed philanthropy more than philanthropy changed Syria,” Wiesner said. “Syria highlighted, among many other things, the need for more focus on preserving higher education in emergencies, and cultural preservation as part of the first-wave of humanitarian relief.”

In 2016, for the second year in a row, the Syrian crisis was the largest recipient of private humanitarian funding, with $223 million going towards the crisis and the neighboring refugee-hosting countries. That is no small feat, as private donors do not typically fund crises resulting from conflicts, said Sophia Swithern, head of research and analysis at Development Initiatives, a U.K.-based organization that analyzes funding for poverty and development-related projects.

“Private donors have traditionally stepped in for high-profile natural disasters, but they didn’t really respond to complex crises,” she said. “What we’ve noticed over the last two years running is that Syria bucks the trend on that.”

A recent survey found that donations to the refugee crisis vary greatly by country. Turkey led the way, with nearly 3 out of 10 of participants saying they donated to refugees, according to the Tent Foundation. Swedish and Greek respondents were also more likely to donate, while French, Hungarian, and Serbian participants were the least engaged.

Tent, which aims to improve the lives of those who are forcibly displaced, was founded by Hamdi Ulukaya, the founder and CEO of Chobani yogurt. He is a signatory of the Giving Pledge, has hired many refugees, and donates to organizations such as UNHCR and the IRC.

Catrambone, from MOAS, said philanthropists like Ulukaya will likely continue to give in order to ease the pain the Syrian crisis has inflicted on so many families. But he said it is unfortunate that many others view the situation first and foremost as a political issue. He said he and his wife have been criticized, even threatened for helping refugees, and MOAS has had to defend against allegations that it was colluding with human traffickers. According to Catrambone, many individuals and organizations have not donated to the Syrian crisis because they do not want to take any political risks, but he has no regrets about helping save lives.

Letting people get involved in different ways may help. Catrambone recalled a conference he hosted that featured the Syrian-American pianist Malek Jandali. Many participants told him afterward that they were impacted more by Jandali’s performance than by anything else at the conference.

“I saw more people engaged because they were moved in a different way,” he said, stressing the need to use creativity to motivate people to get involved.

People from all walks of life have found ways to give to Syrian families. One Canadian couple canceled its wedding celebration and instead donated money to Syrian refugees, and a Canadian man gave his car to a Syrian refugee family settling in his city. A San Francisco woman is sending 5,000 teddy bears to Syrian children through her organization. A Quaker woman in Pennsylvania helped raise $30,000 for UNHCR.

Catrambone said he agrees to some extent with Andrew Carnegie’s comments about the need to educate yourself in the first part of your life, earn money in the second, and give it away in the third. But for those who have made their money at a younger age, there is no reason to wait. Catrambone and his wife were in their early 30s when they were sailing near Italy and she saw a life jacket floating nearby. At that point, there had already been news reports about migrant deaths at sea. They founded MOAS a few months later.

“I looked at my wife and said, ‘We’re so young, we [made money] so early, let’s give it back now. What if we give it all away?’” he recalled. “We’ll have been so enriched with this great feeling of helping people and helping with the most core principles of humanity.”